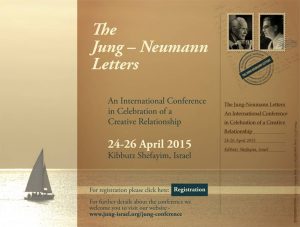

The Jung-Neumann Letters:

International Conference Celebrating a Creative Relationship

I want to begin with two quotes.

The first by my good friend Luigi Zoja who was on the International Advisory Committee of conference but unable to attend:

“…deep psychotherapeutic healing is an ethical act, and that every ethical act is indirectly therapeutic.”[1]

If a man does not judge himself, all things judge him, and all become messengers of God.

– Rabbi Nachman of Breslau (Epigram to Neumann’s essay on Kakfa’s The Trial)

Erich Neumann’s Depth Psychology and the New Ethics was the first notable attempt to formulate the ethical problems raised by the discovery for the unconscious.[2] Jung called his book ‘brilliant…piercing …challenging and aggressive…’[3] He read the book three times in a single fortnight and made dozens of suggestions for a proposed English translation that only appeared after Neumann’s death.

Through the Letters (14 June 1957), we now know that the inspiration for The New Ethics was a series of phantasies that Neumann had during the holocaust, which Murray Stein will discuss. In those phantasies, he experienced the ethical transformation he described in his first masterpiece. Ethical awareness can be transformed in the space of the imagination. Imagining good and evil is central to our experiences as humans and therapists. To stimulate that, I want to begin with an active imagination. Take a moment to consider the following question:

WHAT IS THE WORST THING A THERAPIST CAN DO?

As part of confronting the shadow, we must accept that each one of us is vulnerable to committing ethical violations. Keeping this violation in mind, I will review Neumann’s ideas concerning the evolution of ethical awareness and then to explore the significance of the new ethics for therapists and analysts working today.

THE EVOLUTION OF ETHICAL AWARENESS

Neumann understood the evolution of ethical awareness in terms of three stages. The first stage of “primal unity” parallels the primal unity of mother and infant. In this stage, the group is responsible for every individual, and each individual is viewed as the incarnation of the whole group. What is paramount is loyalty to the group, and not right-and-wrong. Such primal unity provides a profound sense of belonging and solidarity to its members. The whole group shares moral responsibility for every member so that responsibility and revenge is based solely on group identity. As a result, the actual guilty perpetrator need not be punished; anyone in his or her collective will do. Honor killings, suicide bombings or even mass sporting events reflect the moral ideology of primal unity. In a milder form, it might explain why The New Ethics was received so negatively by the Zurich establishment. The conflict was less about the content of the book, but more on Neumann being an outsider.

The Rise of the Old Ethic

Neumann argued that ethics advances to the second stage of the old ethic, came exclusively from introverted intuitive, Great Individuals, such as Socrates or Moses, who experienced a personal revelation from an “Inner Voice”. Such great individuals acted as creative center, as a kind of Self to the Group. As Neumann wrote to Jung in 1933, ‘…great men have always been called upon to exercise discernment and to stand against the crowd.’[4]

The old ethic is familiar from the Spiritual Teachings of the Ten Commandments, the five Pillars of Islam or the Eightfold Way of the Buddha. Its archetypal image is that of the wise, devout, spiritual hero acting as a person of immense self-control. “Who is the hero?” asks the Hebrew Sayings of the Fathers 6:3, and the answer is given, “The one who conquers his [evil] impulses.” It embodies an idealized, absolute, and hence one-sided view of spiritual perfection. The new order does lead to a strengthening of the ego over the tyranny of the unconscious but heightens the conscious/unconscious split. The psyche of the old ethic functions like a absolute monarchy or one party state; psychic life revolves around repression and suppression. Repression necessarily leads to a dangerous cycle in which shadow elements are projected outward, scapegoated and then sought to be annihilated. Neumann experienced this at the outset of his fantasy when he felt commissioned to kill an “apeman”. In Neumann’s time, Chinese, Blacks or Jews in turn became the focus of these shadowy projections. Today, the targets may have changed but the psychic process remains the same.

Suppression, in contrast to repression, is often considered as a mature defense mechanism. Neumann, however, argued that suppression risks leaving the personality flat, with a loss of both creative and animal-like energy, such as “soft men” described by Robert Bly in his classic, Iron John[5], who are “good”, but lacking in resolve and vitality.

Moral life in the old ethic becomes an endless struggle between our good and bad parts, representing the dual and dueling aspects of the human soul. This dynamic is illustrated in the archetypal theme of the hostile brothers that Jung discussed: Cain/Abel, Seth/Osiris, Balder/Loki, Jacob/Esau etc. are the cosmic version of the endless conflict between opposites.[6] The good person aspires, in the old ethic, to be purely good. In Jungian terms, one might say that ego overidentifies with the collective values of the society and so denies his own shadow. In this process, the ego may lose touch with its own limitations in attempting to become disembodied, pure spirit and may become “inhuman”. This is illustrated by a joke I first heard from Avi Baumann: Two women are talking about their husbands. The first says, “My husband is an angel!” The other one replies, “Yes, my husband is not human either! Neumann showed how easily idealism of the old ethics leads to atrocities.

THE NEW ETHIC

The old ethic has no place for evil, which must be resisted and defeated. In contrast, Neumann argued: Evil, no matter by what cultural canon it be judged, is a necessary constituent of individuality[7]… but part of the world to be experienced[8]”.

What, then, is the new ethic?

At the core of the new ethic is the personal responsibility for the dark side. In this context, Neumann presented a patient’s dream in which a hunchback grabs the dreamer by the throat and shouts, “I, too, want a share of your life!” The goal is to grant that dark “hunchbacked” side a share in one’s life. Our fascination with profound evil, in art and literature, from Roskolnikov to Othello, from serial killers to vampire movies reflects our own secret desire to know this hidden, evil side.

In so doing, the ego must give up its innocence and its simplistic victim psychology.

The key commandment of the new ethic is to become conscious. Becoming conscious leads to psychic expansion. Undoing repression reduces the ever-present danger of murderous projection. Neumann summarized distinction between conscious and unconscious evil as follows:

The acknowledgment of one’s own evil is “good”. [To be too good – that is, to want to transcend the limits of the good, which is actually available and possible, is evil.] Evil done by anybody in a conscious (and that always also implies full awareness of his own responsibility) evil, in fact, from which the agent does not try to escape – is ethically “good”. Repression of evil, accompanied, as it is invariably is by an inflationary overvaluation of oneself is “evil”, even when it is the result of a “positive attitude” or a “good will”.[9]

In the realm of the new ethics, real evil lies in splitting good from evil; genuine goodness resides in their acceptance in depth. This attitude is expressed in the Zohar in connection with Job:

“As Job kept evil separate from good and failed to fuse then, he was judged accordingly. First he experienced good, then what was evil, then again good. For man should be cognizant of both good and evil and turn evil itself into good…”[10]

To amplify the need to enter this dark underworld, Neumann used a Kabalistic midrash, based on Rabbi Nachman of Bratzlav’s re-reading of Leviticus 19:18 –

“Love your neighbor as yourself: I am the Lord”. The word, reacha, usually translated as ״your neighbor” or “your fellow” may equally be read as “your evil” (ra’acha) since Hebrew is written without vowels. Using a standard Rabbinic technique, the passage may be reinterpreted to read: “If you love your evil, so too do I, the Lord, love it.” Neumann in this case, was deeply influenced by Kabbalistic teachings concerning the origin of evil and the possibility of repair since: “The most holy sparks are to be found at the lowest level.” (Neumann 1973, p. 126), or as he put it in a letter to Jung, “evil” is only a “servant of God”. (p. 65). Evil is a necessary part of the individuation process. A secure individual needs to do “evil” against the collective values or conventional cultural canon. The individuated person must betray and Neumann used Biblical examples to drive his point home: Jacob deceived his father and Moses committed a premeditated act of murder.

In contrast to the old ethic that seeks to split the spiritual from the material, Neumann felt that the new ethic affirms the Earthy and the Body. Clinically, Neumann understood dreams of flying, or being invisible as attempts to heal the archetypal split inherent in the old ethic. Flying dreams revealed that the dreamer’s ego was “ungrounded”, too far removed from Earth; being invisible meant that the dreamer’s ego is “unbodied”, too removed from Body with all its embodied symbolism. Trying to fly too high, like Icarus, risks a regressive falling back to the Great Mother Earth in a literal or symbolic uroboric suicide.

Neumann believed that depth psychology of the new ethics movements would push humanity toward greater consciousness and awareness of our evils. Thus the ecological movement, of which Neumann was a prophetic forerunner, made us acutely aware of the evil done to environment. Feminism made us aware of the brutal and subtle ways women are oppressed. Animal liberation movement has sensitized us to the evil done to animals. In each case, a new ethic arose to expand our awareness and extend our empathy into new areas. Just this week, I heard that chimpanzee and orangatun were given legal rights in court in Argentina and NY. Future movements, he predicted, will do the same, expanding ethical awareness into areas in which we are currently unconscious and morally insensitive.

Clinical Applications of the New Ethic

Neumann’s vision is daring and revolutionary. As Jung himself wrote, “Neumann’s individual ethic makes far heavier demands on us than the Christian ethic does.”[11]It is elitist and yet profoundly democratic, since new ethic remains open to anyone willing to wrestle with his shadow, as Jacob had done.

The problematic Jungians face concerning new ethics lies in the paradoxical nature of the individuation process. Individuation, the process of becoming more and more ourselves, requires a necessary distancing from the voices of others and the demands of society, as both Jung and Neumann emphasized. They believed the inner voice, the voice of the Self, will guide and show what is right and wrong.

How can we know whether that inner voice is in service of the Self, or merely an ego possessed by the shadow, rationalizing immoral behavior? This is a question that Martin Buber asked.Jung and Buber had a long and ambivalent relationship. Buber spoke at Jung Club in 1923 and at Eranos in 1934. He called Jung a gnostic; Jung, wounded at feeling misunderstood, claimed Buber did not understand psychic reality. Yet Jung wrote that there had never been any personal friction between them.[12] Buber corresponded warmly with Emma Jung, and once with Neumann about his monograph on Franz Kafka; Neumann drew often on Buber’s versions of Hasidic stories. Buber, in Eclipse of God, made a penetrating critique of Jung (and implicitly Neumann). Buber asked, in the wake of rise of Hitler: When one hears that inner voice, how can one tell whether it is the voice of the Self or the Devil?

The great individual may be the moral innovator, but the Ethics is never the exclusive property of the individual, but must reflect shared values of the community. Significantly, Neumann, in the Introduction to Spanish edition, explained that new ethic ‘presupposed a person was “moral” by the standards of the old ethic.’[13]

The challenge is how to apply the new ethics, to our professional lives. Let me start by considering how Neumann’s stages might apply to an ethical violation.

Consider that the ethical violation you imagined is brought as an ethical complaint to your Institute. How would the complaint be handled? In the stage of primal unity, the institute will attack and discredit the whistleblower and rally round perpetrator to fiercely protect the accused, regardless of their innocent or guilt. In the stage of the “old ethic”, the accused if found guilt, would be seen as a traitor of group ideals, scapegoated and expelled while those who remain inside the group are “good”. This splitting of “we are good” and “they are bad” can seem so natural and satisfying to those caught up in the morality complex of the old ethic. Only in the stage of the new ethic would the institute seek a deeper understanding of the significance of the complaint and not to split the Archetype into good and bad, even when perpetrators have done terrible things.

The group psychology of an ethical complaint may be amplified by a Talmudic exploration ofBiblical text of Deuteronomy 21:1-9, dealing with the intrusion of evil:

If someone is found slain, lying in a field…and it is not known who the killer was…. Then the elders …[who sacrifice an innocent heifer in a virgin valley] shall declare: “Our hands did not shed this blood, nor did our eyes see it done…”[14]

In one sense, this is a typical scapegoat ritual. The innocent heifer is sacrificed to purify the guilt of the entire community. But Talmud does not accept this reading of the text based on splitting of innocence and guilt of the old ethic. Instead it asks:

Why do elders declare, 'Our hands have not shed this blood, neither have our eyes seen it'. Can it really enter our minds that the Elders themselves have shed blood! No! The meaning of their statement is to assert that [The man found dead did not come to us for help and we dismissed him without supplying him with food; nor we did see him depart and let him go without an escort or warning him of the dangers along the way.[15]

Talmud extends the scope of collective responsibility. Elders must ask themselves not whether they actually killed the person but rather: Did we do everything to prevent this tragedy. Only then, can the elders, as representatives of the community, declare their hands clean. And so, I argue, we must follow the Talmud in approaching the ethical violations of our colleagues. We must ask ourselves individually and as a collective: Did we really do everything we could to prevent this violationn? Did we fail to “accompany” him? Did we fail to warn him of the dangers on the way? What was lacking in our training or institute ethical culture that allowed this member to go off the track? Each member would ask themselves: what are the slippery slopes in my own practice? How can we revitalize the moral muscles of the society? Synchronistically, why is this evil happening in our institute now or what has this “evil” come to teach us? Neumann wrote that Abraham, who protested against “righteous being slain with the wicked” at Sodom[16], ended with the recognition of the collective guilt, even of the righteous.

But many ethical dilemmas are private and indeed can never reach the public domain. One such private moral event I grapple with is when a patient/analysand tells his analyst something disturbing about a colleague. When this happens to me, clinically, I struggle to understand the meaning of this disclosure within the therapeutic process e..g. why is my patient telling this to me, now and its implications in terms of transference dynamics etc. But within myself, I may feel shocked, defensive and complicit, even dirtied by the disclosure. Such disclosures remain under the seal of confidentiality and thus are all the more disturbing. Jung understood this kind of dilemma when he wrote: “Ethical decision is concerned with very much more complicated things, namely conflicts of duty, the most diabolical things ever invented and at the same time the loneliest…”[17]

Erich Neumann dealt with just such a clinical-ethical situation, shortly after he arrived in Israel. Former patients of James Kirsch, who left Palestine at the beginning of 1935, came to see Neumann for analysis and told him disturbing things about their former analyst. On 27 June 1935, Neumann (16N) wrote to Jung about his experience:

…at the moment I have to keep quiet anyway as the Kirsch matter unfortunately created much resistance to analytical psychology… I am extremely sorry not to be able to discuss with you thoroughly the question of the analysis of analysts, this is my biggest interest, practically and theoretically. There is a lot to be said for the methods of the Freudian school with its training and supervisory analyses although I know that this is more difficult in the case of analytical psychology with its fundamental emphasis on the being of the analyst. Please do not misunderstand me, every analyst makes mistakes and I notice every day how much more difficult, responsible, and important every analysis is, especially here in Palestine. I now have certain insight in Kirsch’s work and I am quite speechless. (About half a dozen patients of his are now with me, those that terminated and others.)…

(I am fully aware of the unreliability of patient’s testimonies. Only consensus makes me more sure.) The worst thing, aside from inflation and curiosity, seems to me his lack of psychological sensitivity that amazes me because he is actually quite a warm human being…

Perhaps he is extraverted and it comes from that. He “goes on” constantly about a “religious problem” and convinces people they have one and thus he scares them off their center. Precisely for Palestine this is a disaster because, for the Jews, the central problem is the religious one. It is possessed by the strongest resistance…

In my work with you – and this was my particular case – it depended, I believe, not on the personal unconscious but, as you also said, on the breaking open of the perspective onto the Self and the collective unconscious, and this consequently thrust me simultaneously into the world and out of myself. With Miss [Toni] Wolff, the personal unconscious came more into its own, in both good and bad aspects…

…the religious problem can be structurally central and the sexual problem secondary, but this must slowly become evident to the patient from the inside through the analysis of dreams, not because he hears it from my mouth. Only the Self must speak in this language, I must, I fear, be unassuming.

I hope, dear Professor, that it will be clear to you that the Kirsch case is important to me not for his sake…

K[irsch]. is only secondary in this. Things are going well for me. My wife and son also. There is much work.

With best wishes

Ever yours,

E. Neumann[18]

There is so much of interest in this letter: the training of analysts (a subject which sadly Neumann did not pursue), differences between Neumann’s own analysis with Jung and with Toni Wolff; relation of the sexual to the spiritual; but what I want to focus on is how Erich Neumann dealt with the moral dilemma concerning what he heard about Kirsch from his own patients. True to the new ethic, Neumann does not demonize Kirsch, but calls him a warm human being; he uses the experience to examine his own work more deeply, admitting mistakes and clarifying issues in clinical practice; and all for the sake of the work in the spirit of the new ethic. Instead of merely criticizing Kirsh, Neumann examines his own shadow in his own clinical work. “Only the Self must speak…” he concludes and adds with symbolic resonance, “There is much work.” Eighty years on, his words maintain enormous vitality.

Neumann’s mature response reminded me of an experience of my own. I recall a female patient, herself a mental health professional who came to me for analysis. Gradually, it emerged that her previous therapist had sexually abused her. Like many victims of such abuse, she blamed herself, and felt unclean, while I felt enraged at this therapist for abusing his power. Caught up in the complex of the old ethics, I wanted him accused, humiliated and to lose his license to prevent further harm. But it soon became clear that my patient had no energy to mobilize for any complaint. She said, “I just don’t have the strength.” I therefore focused on what was right for her even if it was not right for the collective.

After much hard work, the patient eventually came up with a unique solution. She felt that although the therapist had abused her, she was grateful for other good work they had done and decided not to make a complaint but to confront him. She demanded that he never work with female patients ever again, and that is what she did. It was a compromise, but I believe it was a compromise of which Neumann would be proud.

Forgetting a session

Regularity of sessions provides a crucial part of the temenos. But it has happened to me that I forgot a session with a patient. In two cases, the patient called me and I rushed over in time to apologize and salvage something for the session. In terms of the old ethics, I felt terrible and culpable and worried that I have permanently damaged the therapeutic relationship. I promised the patient and myself that it will never happen again. This is the repression and suppression of the old ethics. The new ethics demands trying to understand not only my own hidden shadowy motives concerning this specific patient, but also the unconscious synchronicity of this unethical behavior.

Neumann required that we take responsibility for our own “evil” and come to a deeper understand of why this negative synchronicity occurred; and why now?

Dvora Kutchinski, who is Erich Neumann’s leading disciple, my control supervisor and colleague, told me a remarkable story about how Neumann handled missed supervision session. She said:

I came as usual to him for my session but he was with another patient. “Excuse me. Come again next week.” He said. The next week, the same thing happens. He apologized again and I began to wonder what was going on. I arrive on the third week and he says, “I have analyzed what has happened and I realized you do not need supervision any longer. Twice I forgot. That means you have finished supervision. You are on your own.”

I began to beg him “It is just before your summer holiday, give me one more session. What is your hurry?”

He said, “You will be better off without me!”

It is a sentence I will never forget. That was Neumann the supervisor, who gave you the freedom to grow.”[19]

He had set her free. A few months later, Neumann was dead.

THE NEW ETHIC IN ISRAEL / PALESTINE

Times of great despair may bring forth great hope. Let me end with one more story which illustrates something of the spirit of Neumann’s new ethic.

During the intifada, I was part of a small group of Israelis and Palestinians that included Paul Mendes-Flohr who met regularly in each other’s homes in Ramallah and Jerusalem in what we called a “dialogue group”. I particularly recall one Palestinian man, much younger than me, but who looked much older and had particularly bad teeth. He had served a long prison sentence in Israeli jail as a member of a banned “ Palestinian terrorist organization”. One day, he told us, while in prison, he was speaking with his jailer about their own children and suddenly, he realized for the sake of “the children”, there must be a stop to the endless cycle of killing. He renounced violence at a time when it was very dangerous for him to do so. We felt like witnesses to a “now moment” of transformation. When the Jews in the group spoke of relatives murdered in holocaust, he wept. When we heard stories of life under the occupation, we wept as, for example, when as parents said they preferred their adolescent sons to be in jail, because at least they knew they were “safe”. No member of the group had personally committed any atrocities, but were all members of collectives who did and seemed trapped in a cycle of violence and counter violence based on victim psychology. In this special, safe setting we were able to acknowledge the evil that was being done.

Neumann felt strongly that by digesting our own evil, a fragment of the collective evil is digested as well. He wrote: “But the pre-digestion of evil which one carries out as part of the process of assimilating his shadow makes him, at the same time, an agent for the immunization of the collective…as he digests his own evil, a fragment of the collective is invariably co-digested at the same time…decontaminates evil…“ (Neumann 1973, p. 130). Instead of scapegoating, one takes on “vicarious suffering”. By assuming responsibility, evil itself is decontaminated. Neumann felt we are all partners in the work of repairing the world, “tikkun olam”.

I want to end with an extract of poem by Yehuda Amihai, Israeli’s best loved modern poet who like Neumann was born in Germany but came to Palestine in thirties, which brings together so many of Neumann’s themes:

wildpeace[20]

not the peace of a ceasefire

nor even the vision of the wolf lying down with the goat

rather

as a heart after excitement

speaking of great weariness…

Without words. Without

the thud of the heavy rubber stamp, let it be easy

floating above the lazy, white foam.

Rest for wounds

even not long

(The howl of the orphans is passed on from generation

to generation like a relay race; the baton never falls)

let it be

like wildflowers:

suddenly, because the field

must have it: wildpeace.

"שלום בר" יהודה עמיחי

לא זה של שביתת נשק

אפילו לא של חזון זאב עם גדי,

אלא,

כמו לב אחר התרגשות ;

לדבר רק על עייפות גדולה.

אני יודע שאני יודע להמית,

לכן אני מבוגר.

ובני משחק ברובה צעצועים שיודע

לפתוח ולעצום עיניים ולהגיד, אמא.

שלום

בלי כִתּוּת רובים לאיתים], בלי מילים, בלי

קול חותמות כבדות, שיהיה קל

מעל כקצף לבן ועצל.

מנוחה לפצעים,

אפילו לא ארוכה.

(וזעקת יתומים נמסרת מדור

לדור כמו במרוץ שליחים; מקל לא נופל).

שיהיה

כמו פרחי בר

פתאום בכורת השדה

שְלום–בר.

REFERENCES

Abramovitch, Henry (1995). ‘Ethics: a Jewish perspective’ in Cast the First Stone: The Ethics of Analytical Therapy (Eds. L. Ross & M. Roy) Boston: Shambhala. pp. 31-6.

Abramovitch, Henry (2006a).‘Erich Neumann and the Search for a New Ethic’ Harvest: International Journal for Jungian Studies52 (2): 130-147.

Henry Abramovitch (2006b). ‘Erich Neumann as My Supervisor: An Interview with Dvora Kutzinski’’ Harvest: International Journal for Jungian Studies 52 (2): 162-181. 2006.

Abramovitch, Henry (2007). ‘Stimulating Ethical Awareness: a Talmudic Approach’ Journal of Analytical Psychology 52: 449-461.

Anonymous (2005). “ The unfolding and healing of analytic boundary violations: personal, clinical and cultural considerations” Journal of Analytical Psychology 50:661-691.

Neumann, Erich [1949] (1968). ‘Der Mystische Mensch’ Eranos Jahrbuch XVI/1948. Zurich: Rhein Verlag. Translated as ‘Mystical Man’ in: The Mystic Vision, Ed. Joseph Campbell, 1968. Bollingen. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Neumann, Erich [1953] (1994).‘Die Bedeutung des Erdarchetypus fur die Neuezeit’ Eranos Jahrbuch XXII/1952.Zurich: Rhein Verlag. Translated as ‘The Meaning of the Earth Archetype for Modern Times’ in The Fear of the Feminine and other Essays in Feminine Psychology. Bollingen. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1994.

Neumann E. (1959a) ‘Creative Man and Transformation’ in Art and the Creative Unconscious: Four Essays. Translated by Ralph Manheim. New York: Pantheon Books, Bollingen Series. Reprinted in paperback as Harper Torchbooks. Harper & Row. 1966.

Neumann E. (1959b) The Archetypal World of Henry Moore. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. New York: Pantheon Books, Bollingen Series.

Neumann, E. (1973). Depth Psychology and a New Ethic. Translated by Eugene Rolfe. New York & London: Harper Torchbooks.

Neumann E. (1971) Amor and Psyche—The Psychic Development of the Feminine: A Commentary on the Tale by Apuleius. Translated by Ralph Manheim. Princeton: Princeton University Press, Bollingen Series.

Neumann E. (1972). The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype. Translated by Ralph Manheim. Princeton: Princeton University Press, Bollingen Series.

Neumann, E. (1979a). ‘On the Psychological Meaning of Ritual’ Quadrant: journal of C.G. Jung foundation for analytical Psychology. 9(2): 5-34.

Neumann, E. (1979b). Creative Man: Five Essays.Translated by Eugene Rolfe. . Princeton: Princeton University Press, Bollingen Series.

Neumann, E. (1981). ‘The Mythical world and the Individual’ Translated by R.T. Jacobson. Quadrant 14.

Neumann E. (1989). The Origin and History of Consciousness. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. London: Karnac.

Neumann E. (1994). The Fear of the Feminine and other Essays on Feminine Psychology. Translated by Boris Matthews, Esther Doughty, Eugene Rolfe and Michael Cullingworth. Princeton: Princeton University Press, Bollingen Series.

[1] Zoja 2007, p. 4.

[2] Jung, Preface, 1949, p. 8.

[3] Adler, in Neumann 1973, p. p. 9

Jung in an attachment to his letter to Erich Neumann 75 J, 29 March 1949 wrote:

“Please understand the propositions that follow only as supplementary suggestions. They do not seek to replaceyour text but only to supplement it. This, particularly where you express yourself in a rather activist way. I do not wish to discourage the activism, but simply to emphasize that the shadow or the unconscious absolutely cannot be eliminated and subject to consciousness. We can only learn how a grain of corn must behave between a hammer and an anvil.”(p. 361). Jung reread the text three times in a fortnight and wrote a series of notes and revision proposals for English version. Jung suggested alternative title. See Appendix II.

[4] Neumann’s letter to Jung, 1933, p. 12.

[6] Jung, CW 11, ¶629.

[7] Neumann, Origins p. 352.

[8] 113 N, 14. VI. 57, p. 332.

[9] Neumann 1969, p. 114.

[10] Sperling & Simon, The Zohar, 1931-4, p. 109.

[11] (Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Pages 518-522). Here is full extract: It is an actual fact that what is good to one appears evil to the other. You have only to think of the careworn mother who meddles in all her son’s doings-from the most selfless solicitude of course-but in reality with murderous effect.

For the mother it is naturally a good thing if the son does not do this and does not do that, and for the son it is simply moral and physical ruin-so scarcely a good thing.

You are quite right when you say that Neumann’s individual ethic makes far heavier demands on us than the Christian ethic does.The only mistake Neumann commits here is a tactical one: he says out loud, imprudently, what was always true. As soon as an ethic is set up as an absolute it is a catastrophe.

It can only be taken relatively, just as Neumann can only be understood relatively, that is, as a religious Jew of German extraction living in Tel-Aviv. If one imagines one can simply make a clean sweep of all views of the world, one is deceiving oneself: views of the world are grounded in archetypes, which cannot be tackled so easily. What Neumann offers us is the outcome of an intellectual operation which he had to accomplish for himself in order to gain a new basis for his ethic.

As a doctor he is profoundly impressed by the moral chaos and feels himself in the highest degree responsible. Because of this responsibility he is trying to set the ethical problem to rights, not in order to give out a legal ukase but to clarify his ethical reflections, naturally in the expectation of doing this also for the world around him. In reading such a book you must also consider what sort of a world we are living in.

[12] CG Jung, Letters, v. 2, p. 101. Buber, in fact, did study psychiatry and made contributions to field of psychotherapy, see my “The Influence of Martin Buber’s

Philosophy of Dialogue on Psychotherapy: His Lasting Contribution” in Paul Mendes-Flohr (Ed.) Dialogue as a Trans-disciplinary Concept Berlin: DE GRUYTER, pp. 167-179. 2015.

[13] Neumann 1969, p. 21.

[14]Deuteronomy 21:1-9. New International Version (NIV). The full text is:

21 If someone is found slain, lying in a field in the land the Lord your God is giving you to possess, and it is not known who the killer was, 2 your elders and judges shall go out and measure the distance from the body to the neighboring towns. 3 Then the elders of the town nearest the body shall take a heifer that has never been worked and has never worn a yoke 4 and lead it down to a valley that has not been plowed or planted and where there is a flowing stream. There in the valley they are to break the heifer’s neck. 5 The Levitical priests shall step forward, for the Lord your God has chosen them to minister and to pronounce blessings in the name of the Lord and to decide all cases of dispute and assault. 6 Then all the elders of the town nearest the body shall wash their hands over the heifer whose neck was broken in the valley, 7 and they shall declare: “Our hands did not shed this blood, nor did our eyes see it done. 8 Accept this atonement for your people Israel, whom you have redeemed, Lord, and do not hold your people guilty of the blood of an innocent person.” Then the bloodshed will be atoned for, 9 and you will have purged from yourselves the guilt of shedding innocent blood, since you have done what is right in the eyes of the Lord.

[15] Talmud Bavli, Sotah 46b.

[16] Genesis 18:23ff.

[17] Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, pp. 518-522. Letter continues:… It is an actual fact that what is good to one appears evil to the other.

You have only to think of the careworn mother who meddles in all her son’s doings-from the most selfless solicitude of course-but in reality with murderous effect.

For the mother it is naturally a good thing if the son does not do this and does not do that, and for the son it is simply moral and physical ruin-so scarcely a good thing.

[18] 16N, 27. IV (1935), pp. 110-3.

[19] Abramovtich 1996, 172.

[20] Author’s translation.