“From the age of six I have had a mania for sketching the forms of things. From about the age of fifty I produced a number of designs, yet of all I drew prior to the age of seventy there is truly nothing of any great note. At the age of seventy-three I finally came to understand somewhat the true quality of birds, animals, insects, fishes- the vital nature of grasses and trees. Therefore, at eighty I shall gradually have made progress, at ninety I shall have penetrated even further the deeper meaning of things, at one hundred I shall have become truly marvelous, and at one hundred and ten, each dot, each line shall surely possess a life of its own. I only beg that gentlemen of sufficiently long life take care to note the truth of my words.”

(From Hokusai (1760-1849)who gave himself the name Gakyo-rojin, meaning “Old Man Mad with Painting”, in Lane, 1962, p.260)

In my studio, in the center of a high shelf surrounded by gods and goddesses, witches, mythological people and animals, sits a little red coated fisherman with a green cap, holding a wooden fishing pole with a fish at the end of its line. He has a youthful, ordinary character quite different from the Old Chinese fisherman statuettes found in Chinese tourist shops, that seem to represent the patient wisdom of old age. Sixteen years ago he separated from the rowboat he was originally glued into, when patients needed to position him in a personally appropriate location in the sand tray- on the edge, on a hill, a bridge, near a well, or on sand near a pool, lake, river or sea, but sometimes fishing alone with no water in sight. After a few years of following the use of the fisherman miniature by both children and adults I noticed that patients who used him would do this just once, perhaps twice. This seemed to happen when the therapeutic relationship was advanced and secure, and usually after the fifteenth sandplay session. With several long term patients, some whose sandplay processes I have written about, the fisherman appeared in a later session- from the twenty-second to the fiftieth session (Steinhardt, 2000; 2007c). People related to him as he is- a solitary fisherman, a sport they may not pursue. In reality, most fishermen are boys or men. In sandplay both boys and girls, men and many woman clients use the fisherman, usually once. In a sand picture his fishing may seem incongruent to other events that are depicted. He appears outwardly inactive, fishing in stillness, perhaps withdrawn in contemplation of something elsewhere. He remains in a perpetual potential relationship to a fish that is still in the water (Steinhardt, 2007b, pp. 73-81). This curious one-time use of the fisherman miniature by so many different people awakened a long explorative process that touched the multiple relationships between men, fish and sea, from the concrete level, to the symbolic, to the spiritual, and reconnected me to my own childhood experience of the sea, growing up in a beachfront community in a bay off the Atlantic Ocean. Thus, when I refer in this paper to fishing, I have the sea in mind. Although, in sandplay, all forms of water that a client forms can be used for fishing – ponds, lakes, and rivers- and are important symbols of water as a source of life and a portal to the deep unconscious.

Bernstein (2005) describes a phenomenon that he terms “Borderland”, a world parallel to our reality, of objective, non-personal, non-rational phenomena occurring in the natural universe. Those with “Borderland Consciousness” can receive information and experience that does not readily fit into standard cause and effect logical structure (p. xv). An increasing number of people who have trans-rational experiences that they “know” are real and not “as if” experiences are beginning to divulge these experiences in clinical settings that are able to provide an accepting framework for them. They may have kept their secret for years for fear that our society or clinical settings will tend to pathologize them and brand them as abnormal. Since the Western ego elevates rational process and logos above all other functions it has produced a consciousness that is not merged with nature, “ but wholly cleaved from it and wedded to linear time” (Bernstein, 2005, p.37). Bernstein believes that the “compensatory evolutionary shift” occurring today will lead the Western psyche “in the process of being reconnected to nature from which it began its psychic split over 3,000 years ago” (p.81). Considering the threat of extinction of life as a result of tremendous power struggles between countries, Nature itself, in the name of species preservation if not the preservation of all life as we know it, is leading this process of reconnection to itself, before it is too late (p.81). Western consciousness usually denies the existence of the Borderland dimension of reality. Bernstein, who is a Jungian analyst, accessed this realm by learning from Navajo healers of the relationship between their religion and healing, and about healing as a restoration of the balance and the beauty of the world. Bradway (1997, p. 30) writes about the self-healing of once- polluted Lake Erie: when the cause of pollution was removed, the lake could heal itself. One could then say that a fish as a developing life form depends for healthy growth on the organic balance of the world –the sea womb- it is part of. The human psyche depends on a balanced, non-polluted unconscious for its healthy growth.

A central aspect of Jungian sandplay described by Dora Kalff (2003) is the constellation of the Self, and the experience of centering that in sandplay, can be a numinous and life-changing experience. Amatruda (1997) describes the liminal space in sandplay, a place between the body and the unconscious, a threshold where the unconscious can come to consciousness. Bradway and McCoard (1997, p.9) attribute the power of sandplay to the freedom of actual work with sand, water and miniatures, and the feeling of protection by a “non-intruding, wise therapist whom one trusts.” Jungian sandplay therapists create this “free and protected space” and witness a client’s transition from a state of not knowing what to do in the sand, to the intuitive knowing guided by the Self that brings a sand picture into being. The sandplay therapist confirms that the experience of allowing the psyche to do its work without interference from the ego is part of total human experience, and this will eventually restore balance and self- healing in the world outside the therapy room.

I have noticed that when a client chooses a miniature whose spirit I have personally experienced as part of non-rational reality outside therapeutic practice, it feels not only synchronous with my psyche, but seems also to indicate to me an auspicious moment in the therapeutic process and relationship. For example, the bear, beaver, turtle or grasshopper in my miniature collection represent transpersonal animal spirits for me and I am happy when they are chosen. Unlike the fisherman miniature, these animals may appear more than once in a client’s sandplays. The experience of an objective unconscious, non-rational level of the world is something I do not discuss with most clients, except for those who become aware of it through shamanistic pursuits, or when it is called for, due to a client’s dreams or deep experience and gradual awe of the beauty and numinosity of sandplay. The fisherman miniature in my collection is used just once by each person, and I can not know if a similar miniature in someone else’s collection would be used in the same way. His momentary appearance as a unique symbol in my clients’ sandplays prompted a deeper exploration of this phenomenon that included my childhood experience of fishing as a daily summer activity.

High above the water, standing at the end of a long wooden pier that jutted far out into the ocean from a boardwalk along the shoreline, I and many other people cast drop-lines into the deep water and waited, patiently, usually in silence. During fishing one doesn’t think about symbols, but about catching a live fish. The fisherman can choose his bait but cannot control the deep ocean currents or what will be brought up. Some of the fisherman on the pier may have fished for food, for actual survival. Others perhaps were drawn to spend time between sky and sea, and feel merged with Time and Nature. Some threw the fish back. The sea environment is an infinite space rich in air and wind, water and waves, light and variations on the color blue, a color of intrinsic depth and height, and continual distancing (Steinhardt, 1997). A deep sky blue is described by Walker (1991, p.52) as “the most tranquilizing color of all”. The fisherman’s stillness is counterpart to the distancing of blue and its calming effect. Below, the orderly progression of ocean waves towards shore is sporadically interrupted by waves that turn and clash with waves advancing from other directions, but they all reach the shore. Beneath this, a strong undercurrent recedes pulling water back to the deep. Unseen droplets of evaporating water rise to feed clouds that will produce snow and rain that feed rivers that feed the sea again as waters mix at the juncture of river and sea. The giant water body of the sea moves in all directions simultaneously yet retains its boundaries in relation to land.

The fishermen on my childhood pier were probably not aware that by fishing, they were in contact with two symbolic entities- the sea as symbol of the collective unconscious where psychic life originates (Jung, 1997), and the fish- a fertile treasure living as part of the sea, and considered impermeable to danger. In the great biblical flood with which God destroyed everything except for those on Noah’s ark, fish were not harmed as they were protected by water (Eliahu Ci Tov, 2000). Today’s fisherman may not carve sacred fish on rocks or on totem poles in order to secure magical approval and divine assistance to insure a good catch (Meyer, 1995, p. 40 ; Stewart, 1993; Feest, 2000; Byrgren, 2006). But he may carry an amulet or talisman with a fish on it for general luck, perhaps not consciously worn for enhancing fertility and protection from the Evil Eye (Cirlot, 1996; Gimbutas, 1989, p. 258).

Fishing behavior is consistently still, silent, hoping, waiting, and patient in comparison to the continual movement of the deep sea on all its levels. Sometimes one must unravel a tangled line. The fisherman’s fishing line or string, is the means of access to what lies unseen below the water’s surface. String is also a symbol of “the cohesion of all things in existence” (De Vries, 2001, p. 446). Like a bridge, but on a vertical axis, it connects between what is externally visible – earth and man, and what lies mostly unseen below the surface- sea and fish. It connects the outer silent fisherman and his inner psychic movement roaming the entire realm of the unknown.

Some years ago an American art therapist conducted an “ex post facto” study in which she searched out from her archives, 47 spontaneous drawings of fisherman done by her patients hospitalized for severe depression (Brown, 1993). She correlated the dates of the fisherman drawings with each patient’s psychiatric file and found that the drawings appeared just when the patients began to show improved functioning and felt calmer, more in control and more optimistic about life. In their therapeutic process,the fisherman seemed to represent the patient’s unconscious awareness of their capacity to focus energy on independent self-nurturing, gaining deeper understanding, and the search for creative power (Steinhardt, 2007a).

The sandplay fisherman is faithful to the general traits of fishermen- solitary, silent, patient, waiting. His single appearance in each sandplay process is discrete, quiet and unassuming, and he is never an ongoing symbol for any one person. But as a recurring aspect in my work as a sandplay therapist, he demanded more attention. I was being invited to fish through my own sandplay photo archives, and reconnect to my own writings to decipher something that I did not know I was looking for. I reviewed more than fifteen sandplay cases as a general affirmation of the phenomenon, without intent to gather information for research. Both boys and girls used the fisherman on land, and two girls placed him in a boat in water. Women usually seated him on the sand at some height above the water, sometimes near or on a bridge. I found three instances where the sandtray edge was used, by a man, a nine-year old boy and a 40 year old woman.

I looked through the case of Wanda, a young woman in double mourning- for a brother killed in war and for a stillborn first son (Steinhardt, 2000, p. 207). After the traumatic first birth, she remained infertile for a year and a half. During her second pregnancy she lost confidence that she could successfully carry a child to term and deliver a normal baby. The fisherman appeared in her fiftieth sandplay when she was six months pregnant for the second time, and had begun to feel a positive change and more confidence that the outcome of this pregnancy would be a success. Wanda commented that his face was “stupid” but she needed the fisherman and his red color. “To sit and fish and wait suits me”, she said. (p. 207). The fisherman fishes on the right bank of a squared central body of water surrounding a small island (a Mandala) with a fertility goddess in the center. On his hook is a small fish whose yellow color could represent rational intuitive thinking. There are many fruits on all areas of the sand, and on a wagon laden with fruit. The fisherman was one of several new positive male presences –it was the ego able to provide psychic nourishment from the unconscious, together with food- self-nurture, from the earth (Figure 1).

Nina, a forty eight year old woman in her third year of therapy used all the sand in her fifteenth sand picture to create a bridge-shaped island with a red canoe passing underneath. The fisherman is perched on the right side of the island uninvolved in the boat’s passage (Steinhardt, 2000, p.148). I focused on the boat’s transitional passage and Nina’s sensation of birth, acknowledging the fisherman as a numinous addition to the “emotional experience of the basic theme of birth and transformation” (Figure 2).

In a presentation for the International Sandplay Conference in Ittingen in 2001 I examined how spending time in the natural beach environment (specifically Israel, with its Mediterranean coastline) influences a client doing clinical sandplay. Jung, in his essay “Mind and Earth”, (1951/1991) “speaks of the mind’s adaptation to the earthly environment, noting the differences between his American and European clients, in their physical behavior and emotional expression. He saw the earth itself as molding these difference by conquering, in a sense, the unconscious of those living on it” (Steinhardt, 2007a, p. 17). The importance of the power of Nature and wilderness to heal itself and restore balance to the earth if given enough time is discussed by Wheelright and Schmidt (1991). They consider the imprinting of Nature on the inner world in childhood and state: “If we do not honor and experience the wilderness outwardly, we cannot find that inward healing, balancing level in ourselves (p. 50). Thus, since Israeli beaches are attended throughout the year by much of the population, aspects of beach life would filter into and influence sandplay behavior in the clinic. A description of beach life and “beach consciousness”, and a comparison of sand, water, and creative activity in both places, ended with some photos of early morning fishermen and with some clinical examples featuring the fisherman miniature as a connecting symbol in sandplay. The fisherman symbol again seemed to “indicate a preparation for, or ability of, the ego to be in contact with the unconscious and bring up material from the deep unconscious sea” (Steinhardt, 2007a, p. 27).

I did not address the real fisherman’s persistent connection to the sea as unconscious inward self-healing and rebalancing, or restoring harmony aided perhaps by ingesting fish, the offspring of the sea who remain connected to the source. Sea creatures begin and end their lives in water. They never leave their source as do plants or animals beginning in seeds, eggs or wombs and leaving them for a different sphere. Eating fish is to return to the source. The sages of the Mishnah- (the first written text of Jewish oral tradition of debate from about 200CE) are called "fish of the sea", because no separation exists between them and the spirituality of the Torah just as there is no separation between fish and sea.

Jung too spoke of the inter-relationship of all things. In his Visions Seminars, he states: “Fishes are living units in the sea; they are not at all like it but they are contained in it. Their bodies, their functions, are marvelously adapted to the nature of the water, water and fish form a living unit. As the fish can say “I am the sea”, then the sea can say “I am the fish” (Jung, 1997, pp. 753-4; Sabini, 2002 , p.206).

My fisherman miniature was persistent with me. A brief presentation in a seminar about the fisherman as a pivotal symbol in sandplay, led to a longer article featuring the fisherman symbol, intended to introduce the relevancy of sandplay to art therapists. Several sandplay examples of the fisherman encouraged art therapists to become more familiar with symbolic depth and amplification with the symbols that may appear in a client’s artwork (Steinhardt, 2007b).

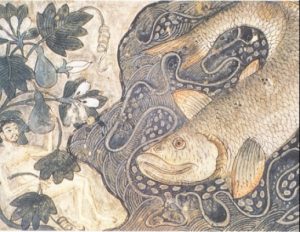

A theme of the Cambridge International Society of Sandplay Therapy Conference (2007c) was sandplay and culture. I presented the ten- year sandplay process of a Jewish Israeli woman of Moroccan origin, whose mystical North African heritage included a deep and ancient belief in a powerful spirit world that could give or take life. When I was immersed in writing, I realized that the fishermen appeared here too- just once, in her twenty-third sandplay, out of fifty- five (Figure 3). Thereafter a succession of dreams and sandplays featured fish as a transformational symbol, beginning with a tiny tarnished metal fish in a dream market, to a dried- out (mummified) fish in a dry well, to the return of flowing water and finally a rebirth in sand of a fish and waves as one unit (Figure 4). She recalled Jewish traditional belief in fish as a symbol of fertility, abundance and Good Luck.In Hebrew, the letters of the word Fish (DaG) equal the number seven, a lucky number. When you reverse the letters it spells GaD- meaning Luck. Thus, she explained, fish is traditionally eaten on the Sabbath for good luck. She accepted her right to be lucky in life, willing to live and use her talents, and she revisited her original Moroccan home with her family.

I looked up at the fisherman on the high shelf in my studio and saw that I had placed him among divinities, above all the more “ordinary” miniatures on the shelves below. The lower shelves became the sea of the unconscious and I imagined him as fishing for treasure among the other objects below, just as a client after using the fisherman has the entire symbolic world of sandplay at his or her disposal when the time is right. Kalff, (2008. p.129) in a review of Dr. Kawai”s book “Buddhism and the Art of Psychotherapy” writes of Dr. Kawai’s belief that as a therapist “he found it important to master a capacity to move from a superficial, more personal level of consciousness to a deeper level, free of discriminating thought, a transpersonal or cosmic cognition.” He also distinguished between “strong transference” implying strong feelings such as hatred or desire, and “deep transference” related to what the Japanese call hara, the center of the person. In his view it is the “deep transference” which is crucial for healing”(p.129) . This may be the right moment for the fisherman to enter a sandplay process. There has already been some development of basic trust and a good relationship and the client’s ego is stronger. Through work in the sand, the superficial transference has evolved into a deeper transference, that touches the Self of therapist and patient, which is in our center and around us. The client sees the fisherman and places him on sand or on a rock or bridge, all of which provide a base on a horizontal axis. The fishing line supplies a vertical axis of connection from above to below. As energy, these two directions form a “cross” of which the fisherman is the center. It is interesting that Weinrib (1996, p.24) says that

“the critical element of the cross is how well the center holds together. In my

experience, the cross tends to appear in sand pictures well into the sandplay

process when a strong center has been coagulated, when there has been some

constellation of the Self so that the ego feels supported and sufficiently developed

to withstand prolonged tensions, that is, tension created between powerful

opposing personal values.”

The fisherman as center of these two directions, is secure enough on land to initiate the fishing connection, the urge to get closer to the Self, to be open to everything that will come to him from the unconscious sea, and not fall back into the water. Fish can be messengers of the contents of the unconscious, closer to the Self than the ego can be. The fisherman miniature reveals the capacity to fish alone. He represents a state of constant expectation and not-knowing, and sudden fulfillment, holding the tension of the opposites. He represents the role of patience and depth in therapy, of not finding solutions too quickly that would prevent descent to the depths. He might be a longing for a return to the source of creation, and independence from that source during life. The fishing line is at once the separation from the source and reconnection to it. It is the ability to enter the flow between consciousness and the unconscious, between Ego and Self. The fisherman is used as a symbol just once, as this ability then becomes internalized and constant in the sandplayer’s psyche.

Jung states that symbols created by the psyche “are always grounded in the unconscious archetype, but their manifest forms are moulded by the ideas acquired by the conscious mind” (Jung, 1956, p. 232). An archetype takes form, and becomes an “image” in the realm of consciousness, a symbol that “best defines or formulates a relatively unknown fact, which is nonetheless known to exist or is postulated as existing” (Jung, 1989, par. 814).

List of References

Amatruda, K. (1997). The world where worlds meet. Journal of Sandplay Therapy, 6, (2) pp. 19-20.

Bernstein, J.S., (2005) Living in the Borderland: the evolution of consciousness and the challenge of healing trauma. London and New York: Routledge

Bradway, K. (1997). Self Healing. Journal of Sandplay Therapy. 6 (2) 29-48.

Bradway, K. and McCoard, B. (1997). Sandplay- silent workshop of the psyche. London: Routledge.

Brown, R.J.(1993). The fishing image: A preliminary study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 20 (2), 167-171.

Byrgren, F. (2006). Norwegian rock art. Retrieved October 22, 2007 from Don’s Maps Web site: http;//donsmaps.com/norge.html.

Cirlot, J. E. (1996). A dictionary of symbols. London: Routledge.

Ci Tov, E. (2000). Sefer Hatoda’a (Hebrew- Book of Knowledge). Jerusalem: Beit Hotsa’at Sfarim.

DeVries, A. (2001). A dictionary of symbols and imagery. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V.

Feest, C. F. (2000) Ed. The cultures of Native North Americans. Cologne, Germany: Konemann Verlagsgesellschaft

Gimbutas, M. (1989). The language of the goddess. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc.

Jung, C.G. (1931/1991). Mind and earth. Civilization in transition. London: Routledge (CW 10, par.49-103).

Jung, C. G. (1956). Symbols of transformation. The collected works of C. G. Jung. (Vol. 5). London: Routledge.

Jung, C.G. (1989). Psychological types. The collected works of C.G. Jung (Vol.6). London: Routledge.

Jung, C. G. (1997). Interpretation of visions. Ed., Claire Douglass. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997. 2 volumes. (Previously published as The Visions Seminars, Zurich, Switzerland. Spring Publications, 1976.)

Kalff, D. M. (2003). Sandplay, a psychotherapeutic approach to the psyche. California: Temenos Press.

Kalff, M. (2008). Review: Buddhism and the art of psychotherapy. By Hayao Kawai. Journal of Sandplay Therapy, 17, (2), pp. 126-129.

Kawai, H. (1996). Buddhism and the art of psychotherapy. Texas: Texas A&M.

Lane, R. (1962). Masters of the Japanese print. London: Thames and Hudson.

Meyer, A.J.P.(1995) Oceanic Art. Koln, Germany: Konemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbH:

Sabini, M. (2002) Ed. The earth has a soul: The nature writings of C. G. Jung. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books.

Steinhardt, L. (1997). Beyond blue: the implications of blue as the color of the inner surface of the sandtray in sandplay. The Arts in Psychotherapy 24, 5, 455-469.

Steinhardt, L. (2000) Foundation and form in Jungian sandplay. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Steinhardt, L. (2007a). Sandplay in Israel, a coastal Mediterranean country. Sandplay and the Psyche: Inner Landscapes and Outer Realities. Weinberg, B. & Baum, N. (Eds.) Toronto: Thera Arts.

Steinhardt, L. (2007b). The fisherman: A connecting symbol. ANZJAT: Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art Therapy, Vol.2, 1, 73-81.

Steinhardt, L. (2007c). Delphine: The influence of Moroccan Jewish mystical belief on the survival and sandplay process of an Israeli woman. Unpublished paper. Cambridge: International Society of Sandplay Therapy Conference.

Stewart, H. (1993). Looking at totem poles. Vancouver/Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Walker, M. (1991) The power of color. New York: Avery

Weinrib, E. (1996). The shadow and the cross. Journal of Sandplay Therapy, 5 (2) pp. 23-29.

Wheelwright, J.H. & Schmidt, L.W. (1991). The long shore: A psychological experience of the wilderness. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.