Naomi Nir’s Account of Her Analyses with Erich Neumann and Emma Jung,

Jung Journal 18 (3) Pages 11-47 | Published online: 08 Aug 2024

ABSTRACT

In Part Two of “The World Broken into Splinters: Naomi Nir’s Accounts of Her Analyses with Erich Neumann and Emma Jung” the author describes Naomi Nir’s analysis with Mrs. Jung via her intense journal or Notes. She is tormented by her resistance to Jungian psychology, which she relates to more as a dogma than a theory, but her conflict may have been an animus defense against a deeper connection with her analyst. In addition to her analysis, she remained in intense contact with her “inner Neumann”; with “she,” an inner wise old woman; and her creative artwork as a kind of art therapy. Ultimately, she was able to return home to gather the splinters of her life into a restored vessel, working at archaeological sites and ultimately becoming a wounded healer using art and play therapy with disturbed children in a children’s home in Jerusalem.

In Part One of this article, I described Naomi Nir’s experience in analysis with Erich Neumann, which concluded in 1949. In 1952, Naomi, suffering considerable physical pain and discomfort, consulted a physician in Tel Aviv. After examining her, the physician told her that symptoms were not based on physical ailments but were the results of emotional conflicts. He recommended psychological treatment. Naomi then contacted Erich Neumann by letter asking for his advice. Neumann replied that the only person who could help her was Emma Jung, the wife of C. G. Jung, who like Neumann’s own wife, Julia, was also an analyst.

Naomi traveled to Switzerland in April 1953 and made arrangements to start seeing Mrs. Jung for analysis. In her entry for April 5, she is already thinking of showing her paintings of Arabs and her diaries. By April 27, she has rented a room in a pension in Zürich and her diary refers to a Zürich newspaper in the wastebasket of her room. The next day, she reports that she has taken a short train ride from Zürich to Küsnacht to see Mrs. Jung. It is not clear whether this was her first session, but she seemed to leap into the analysis, telling Mrs. Jung about her “dreams of Neumann’s dream-house” as well as “how she tried to kill myself ” when E. [Neumann] “turned away” from her, and how she felt she had lost contact with “she,” an inner feminine voice that often speaks like a wise old woman, as described in detail in Part One.

Naomi also studied at the Institute of Applied Psychology in Zürich and took at least one course and participated in some activities at the Jung Institute. She was deeply involved, often critically, even to the point of torment with Jungian thought. During the year of her analysis with “Mrs. Jung” (as she called her in the Notes), she wrote a very detailed account of the experience that runs to 430 typed pages. Her journal includes detailed accounts of her sessions, in some ways clearer than her account of her analysis with Neumann. As with Neumann, Naomi gives poignant details of her difficulties and her own discontent with analysis. At the same time, large portions of her journal of her time in Switzerland are given over to moving reflections and memories of Erich Neumann, whom she calls “E.” The text also includes many intimate “letters” that she wrote to him, but were apparently not sent, yet were part of her dialogue with her “inner Neumann.” She also recorded in her Notes letters sent and not sent to Mrs. Jung. Therefore, it is important to read Naomi’s account of her time in Switzerland in analysis with Mrs. Jung against the background of her analysis and ongoing emotional dialogue with her first analyst, Erich Neumann. Naomi, apparently, shared her journal with Mrs. Jung who made no comment about them. Naomi had ongoing active imagination inner dialogues with “she.”

Naomi stayed in Switzerland until May 1954, when she returned to Israel. She does not describe the ending of the analysis in her Notes. But on the entry for April 6, 1954, Naomi writes she has been without analysis for three months, suggesting she stopped seeing Mrs. Jung at the beginning of January 1954. Considering the vast amount of material, I have decided to present Naomi’s material thematically, rather than chronologically.

Analysis with Mrs. Jung

Music and Art

Music, both outer and inner, played a crucial role in Naomi’s life, often providing the sole source of comfort. She was also extremely knowledgeable about music, mentioning Grieg, Beethoven, and other composers. At the beginning of April, she says: “My life is haunted by this inner music … ” Music and musical metaphors run as a leitmotif in her Notes.

While she was in analysis with Mrs. Jung, she also painted intensively, sometimes all night or even ten paintings in a single intense day. Her thoughts about her paintings were often then linked to musings about analysis. On April 4, Naomi speaks of wanting to show Mrs. Jung her paintings and writing about the impasse concerning the analysis, which centers on her criticism of the “Jungian system”:

I thought again to show painting of “Arabs” [a Yemenite, a “dark one,” she says later] to Mrs. Jung with the diaries that go with them. I now recalled that in earlier diaries I kept struggling against the Jungian way. I thought now I would give it to her and try to explain how I found myself fighting against the “Jungian system” … I realized I could not explain, not understanding myself what I was groping for.

In my imagination I spoke to Jung Footnote1 now, saying that I kept feeling there was some other way, but I do not know it and cannot help even myself (let alone another soul) find it … But I cannot give Mrs. Jung (or to Jung) writings that struggle against him—one cannot do anything so ungracious … . Was my acceptance now of the analysis a pretense even to myself, while in my heart I was against it?

I think part of the bitter conflict around going to Mrs. Jung is centered here.

I have wondered whether Mrs. Jung could help me to go “her” way, to find what this means …

I do not know the “way” [and] that haunts me, that I unconsciously compare other ways to it and in my heart reject them because they are not “it” … if I were not damaged—something … cannot be lived naturally and simply because of what happened to the “core” in me … this song has haunted my life for weeks now

Skylark …

I don’t know if you’ll find these things

But my heart is on your wings …Footnote2

Throughout her journal, Naomi describes intense emotional reactions to her many art projects. On May 17, 1953, she writes:

… sculpting two heads til 6 am. Paintings …

I recalled that I realized at Mrs. Jung’s yesterday, that I still love “normal life” though it denies any “place” to the inner forces in its scheme of things … desirable but inner life becomes devalued …

Song of the bird has begun to sing in me …

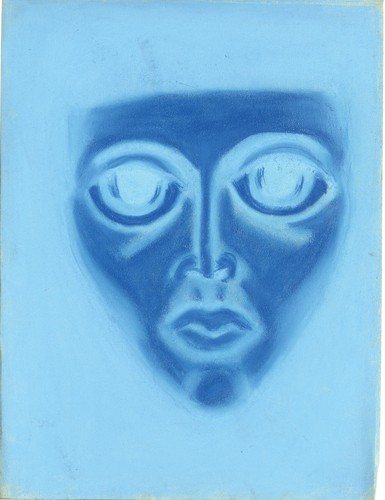

Naomi Nir, Yemenite Child

One of her important paintings is a blue Yemenite Child, completed after a “night of dark dreams, dreams of Yemenites, rough boys, and problem children … ” The painting reminded her of a Yemenite Jew she had painted in Tel Aviv who

… was cleaning my flat and who told lies. Gradually—as the animosity against her had begun “to take on meaning”—the matter of going to Mrs. Jung and not admitting my “fighting against Jung,” came up. This was the “lie” I was proposing to live. This was one of the problems which made my going to Mrs. Jung a horror to me—acting on me like an illness when I was not aware of it, and also when I was aware of it as an unendurable situation.

On the other hand, her paintings reflected the positive impact of her analysis, with Naomi saying, “so many positive things, so many associations of healing and light and love, have been connected with Mrs. Jung,” and even the song of a bird within. Then abruptly, looking at her own painting triggers an almost psychotic-like reaction:

But I recall the distress which the Yemenite Child had brought. It had seemed at first a child, then suddenly an old woman; and the thought kept coming up, unbearable: “She is not at all a child! She is not as innocent as she seems!” And I felt this had some reference to my “innocence” with Mrs. Jung—but I could not understand what this could mean, how my innocence [was] false. I was at a “place” where I was aware of “her,” seemingly, where I was innocent, seemingly. The “associations” that came up bespoke a true “purity of heart.”

Such anguish came with this painting.

Upon her return to her apartment, Naomi has another burst of creative energy as well as fear of her own destructiveness: Her painting is like a kind of art therapy, bringing conflicts to the surface and helping her work them through. Through the painting, Naomi is finally able to come to a decision: “I don’t know whether it was before or after this [another] painting that I telephoned to Mrs. Jung to say that I would come that day … the question of the struggle with “the Jungian way” bursting into consciousness.”

Later that day, Naomi continues her artwork and describes a dramatic visit to Mrs. Jung:

5th painting after visit to Mrs. Jung, “that last difficult visit when the dreaded subject came out.”

I recall, in the train to Küsnacht a feeling of panic had seized me. I “saw” crashes that destroyed or maimed me; frightening image of crashes and collisions, kept rising within me and I recoiled from knowing them.

… Nightmare, turning against Jungian way “but I was caught in the trap of lies”—I felt that because I had these things in my mind I lost my innocence. To be friendly and as-if truthful, in talking to Mrs. Jung, would be living a lie because of unsaid things.

Unhappy beyond words, I went to her. I tried to hold to my awareness that I must not hurt her or give her darkness of my doubts, that I must keep things to myself till I can “pass through the negativeness to the positiveness beyond.” But the “charge” was working in me, and the tormenting “secret” came out.

Mrs. Jung must have been utterly unprepared for what I said. At first she listened and answered in the quiet way she has, but in the end as if knocked out of her position by all this unexpected criticism, she said: “Perhaps it is better that ‘she’ should do your analysis. From what you have said till now, all ‘she’ says seems right … ”

I left feeling, as I closed the door behind me, that the door has closed behind me forever—I was departing alone. And something so brittle, so cold, so “lucid,” swept over me that I seemed to see myself walking to the Pension, taking out the poison and putting an end to my life. All was over.

I walked on, then suddenly realized that I was really in danger, that a coldness had come over me that was terrifying in its “lucidity” and finality. I turned back to Mrs. Jung’s house, and wrote her what had come up, and left the notes and the paintings and the dreams (which she had not read). I had come back to leave something of mine behind, that I should still be partly in her house—against the terrible finality of taking back all my things and closing the door behind me.

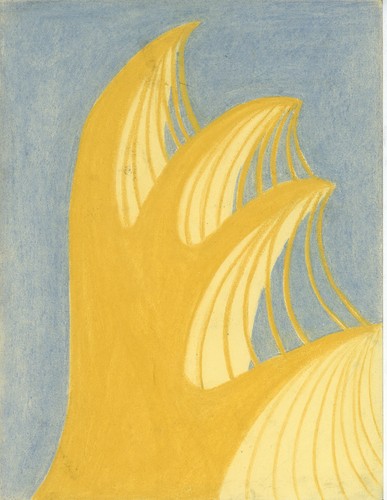

That evening I painted, in deep trouble, too desperate even to struggle. The painting was a dark thing. The darkness (the “dark” waters,” which only that morning I had painted penetrating into the “outer circle”), now rose threateningly to my stronghold, the “place of light” (“to the right above”). In two sharp menacing “jaws” the dark dragon pushed upwards. Three grey forms, rounded “male-forms,” pressed downwards, pushing the dark waters back.

I felt that somewhere the depression was fighting back even then, was putting up a fight against the encroaching darkness.

I looked at this painting, knowing it for the darkest most desperate painting I had painted till then.

In this moving and intense passage, we get a real “feel” for the analysis. Naomi’s intense fear of her own destructiveness expressed as fear of train wrecks shows her grandiose side. Naomi’s over emphasis on “theory without love” makes Mrs. Jung into a withholding negative mother. Naomi’s emotions swing from suicide to reconciliation, whereas Mrs. Jung’s calm composure does seem to provide a good-enough container for the temenos.

In the next entry, Naomi touches on anguish and the yearning to belong:

There is anguish today. I cannot live with myself like this.

… if I am not “one of the Jungians” I will not “belong” anywhere, and to “belong” somewhere is still a longing in me … that I will be so alone, that I will not “belong” anywhere.

Mrs. J. distress at Dr. B lecture and Jacobi’s bookFootnote3 … going round in the pieces, going after them one-after-the-other … with me, mind was inferior function …

Dream: [It is] late, time to leave Jung’s house, go home. I am still in their house but it is time to leave.

Demon Lover: “She” and Mrs. Jung

A dream of the devil at the end of May allows Mrs. Jung to make some progress in getting Naomi to deal with shadow issues:

Dreams so friendly to the devil. Ask Mrs. J, But what is devil? Fallen angel?

She replied Devil as often being seemingly negative, holding something of importance behind him.

Toward the end of the year (December 30, 1953), Naomi returns to this theme:

… I then recalled that when, some time ago … Mrs. Jung … spoke of the “demon lover” … I began to think that inner companion was such a demon lover. This brings up the memory of reading (soon after, I think) in Jung’s book the pages which explained Miss Miller’s pre-occupation with the inner things as caused by her desire for the ship’s officer, a desire she couldn’t fulfill. I was to wonder then whether the inner companion was a substitute for … E.

Indeed, a few days later, Naomi, for the first time in her Notes, is able to speak clearly about her own mother:

Mother … cold and calculating

[I speak] In imagination to Mrs. J

How E. had once spoken slightingly of someone … that made me realize he sees patients with other eyes than the rest of humanity … excluding them from what the insights bespoke … I was struggling again with the “theory” divorced from life, theory that is understood and enlarged “in a closed space” but whose implications for life are lived, are somehow lost sight of or not realised … .

I thought that perhaps “Jung’s way” was “the Devil” to me so often because it has somehow this partial nature; … in some way leaves out the life-side, the “living” which would go with “awareness” if they were not split apart. I felt that “she” somehow represents the “level”—the wholeness—where the “awareness,” the “being” and the “doing” are not separated, where the “theory” is an indivisible facet of life’s wholeness in a human being.

And again, over the next few days, she is caught up in what is now a familiar “agony”: “The conflict over my relations with Jung’s teaching is coming up. It is truly an ‘agony.” Synchronistically, both Neumann and Mrs. Jung gave Naomi the very same Lao Tzu poem, presumably to encourage her to enter more deeply into the present, as in his paradoxical phrase, “By letting go, it all gets done.” Naomi expresses the contrasts between Mrs. Jung and “she”: “To her, charge in me is always great; when I am near ‘her’ the ‘charge’ is good and beneficent, but if I get hurt and cease feeling (and feeling is so bound up with ‘her’ in me) the ‘charge’ runs into ‘animuses’ and ‘over-activation of the mind.’”

Naomi continues with a wish that “analysis should be the ‘place’ where one contacted ‘her’”:

I also recalled what it meant to me that in the analysis with E., I had learned to contact “her.” I tried to think out these two seeming-opposites, but became confused. … analysis is for those who do not know “her”— … that is why I “recoiled” so after talking of Christ to Mrs. Jung, why I felt those things were not for talking about. Perhaps that is what brought the protest-dream against the “reporter” who wants to photograph me, and the dream of the rough me (“me”!) who “sells flesh” … who [has] pieces of cut-up fish upon the counter (“cutting up” = analysing)—fish smoked or salted (“smoke” and “salt” both being connected with “consciousness” of the analysis, recalling the desert and with “columns of smoke,” and “Dead Sea” with its saltiness). … bad to have these awarenesses … I said: “If a bird had the ‘awareness of a human being—it might be very fine, perhaps, but the bird could not function as a bird, as it was created to be and do.’ … forbidden awarenesses” … utterly unconnected with one’s functioning at a human level …

And again on June 20, 1953, Naomi experiences the clash between “she” and Mrs. Jung:

All my preoccupations with “her” way, have no reality to Mrs. Jung, so how can she help me find what it is that has kept me in this situation so alone and apart from the life about me?

… yesterday she spoke as if they were all to be ignored, and I must try to live a “natural life.”

I told her this is how “my sister” in me sees it: this normal life is life; the pre-occupations with “her” and “her” way are a kind of disturbance to the right way of living. But to see so is to go wrong in me; because then all that is connected with “her” who is the deepest greatest “value” in me, becomes meaningless, it is superfluous.

The next day, June 21, 1953, Naomi writes a letter to Mrs. Jung trying to understand the impasse between them:

Dear Mrs. Jung,

… you say perhaps I should not come to analysis, or rather should not have an analysis … I keep thinking: how can you help me when you don’t want me … without a bond?

If you find it hard to “take” me … there is little hope with someone else … To start seeing someone else? I don’t want to … to come when you make me feel I disturb you will undermine me. It is hard enough as it is, coming to you with things as they are within me. I seek the “answers” outside, ever and come to grief. It was of this I was writing in the unsent letter; that I seem to be ever seeking to find “her” in the analyst … as in dream … I have to blunder … coming up against all the things that keep me from living “myself” outwardly and then “answers” would come up gradually from within.

I tried to say this to you last time, and you said: “What kind of an analysis is this?” I keep wondering how you think it should be …

Naomi has a real emotional tie to Mrs. Jung and so bitterly, if unconsciously, fears rejection. But at the same time, she resists Mrs. Jung’s agenda of bringing her down to earth. This stalemate leads to “wanting to die.” Later, on June 6, Naomi speaks to Mrs. Jung about Neumann and the nature of analysis:

More dreams … mandala with white rose in center … I recall now that I felt after talking to Mrs. Jung of E., that to her too (and to me as long as I saw with Jungian eyes) such deep relationship is some kind of involvement in projections, etc. … Dream my bed was tidy and whether I am a nun …

The white rose mandala and dream of “whether I am a nun” reflects whether Naomi might have done better with a spiritual vocation as a religious sister in which innocence and devotion were valued above all:

Distressing feeling of “pretended innocence.” The suggestion of pretense is unendurable.

… If I could stay within this world yet go (“alone”) along my path—as E. is doing, adding to himself and so enriching and changing—I would be happier, I would not be so alone.

… I dreamt of E. last night … who loved deeply in his inner life yet did not withdraw from the world.

She is again deep in despair, fearing suicide and madness:

I seem to be nearing a desperate crisis. Fear of madness came to me yesterday, and this night I dreamt I might die soon and I was trying to assure the future care of [my daughters] … another dream Christ appeared, connected with a newspaper. It means “agonies” I wondered if it referred to writing. I wondered whether I should go on alone now by writing and work through the crisis like this …

In the same entry, Naomi writes another letter to Mrs. Jung contesting the idea of transference, while expressing her yearning to belong and yet not belonging.

Dear Mrs. Jung,

… my “fighting” analytical psychology and its “world” … brink of madness … work through this trouble with someone who knows the “Jungian way” as only a Jungian can know it, yet be somehow outside it; … hangs over me like a guilt … that I know not how to cope with nor how to get out of—except by keeping away from you and all Jungians. And when I decide to do this, I am driven back seeking for help.

… what I am struggling against. It must be something within me …

The day you telephoned and asked me to come to your garden whenever I want to, was the beginning of the darkness which rose in me as a fresh wave. I wanted to come, oh, I wanted to come. But some unbalance rose and rose … culminating in the dream of “mountainous seas” and the bearded man gone mad who thundered that “perhaps it has to be so, to bring freedom to others.”

… I wrote to you (on your holiday) and wanted to send some of my “pages,” but was held back, I know not why.

… My friendliness—my longing to give and receive warmth, to accept and be accepted—comes up in me like a lie (even if I am unaware of it at all, an undercurrent of distress and unbalance is always there), … eroding my very core. … became activated in me through E. Somehow (perhaps through the intense workings of a deep analysis combined with a deep personal level). They seem to be his problems with which I became activated …

I have tried to accept these things in me. Yet I am always fighting them … When I try to accept, the “fighting” increases; seemingly I tend to accept also something I may not accept.

The next entry shows how well acquainted Mrs. Jung is with Neumann’s theory:

I have tried to paint again. I am too driven and peaceless for it now …

Mrs. Jung asked me, during the last visit … if I thought the “horse” that bites me in the dream could be what E. called the “uroboros.”Footnote4 I told her I have never thought like this … [to me] horse suggests energy of earthly life, of “normal life.”

… I tried to explain my feelings … that the “earth mother’s” earthliness was too concrete … not the real earth in which things grow. … to me “the mother” was not “a state of awareness” but somehow a concreteness.

But yesterday I suddenly seemed at times to see the “mother’s earthiness” as a state of awareness, the “concreteness” was in the eye that saw things thus … “inner” and “outer” confused in my images as they invariably do when I try to grasp these things.

The words “verschluckende mutter” [“choking mother”] kept coming up. I recalled they had come up at times since that visit to Mrs. Jung.

The next day, June 29, Naomi is reflective about how her uniqueness alienates her: “ I seem to “perceive” differently from others, and I fear this may be some sign of madness … which makes me a stranger in my own age and surroundings.” On July 2, Naomi feels caught between “she,” her inner guide, and Mrs. Jung, her analyst: “I wondered suddenly whether I was tending to give up ‘inner communion’ and accept Mrs. Jung’s guidance instead—to accept an outer guide instead of the difficult one.”

Naomi Nir, Seeing the World from Outside

Parental World

At the beginning of July, Naomi reported a number of significant dreams:

Dream: I was kneeling facing leftwards. A man clad seemingly in metal, let down the guillotine-blade across my neck. My head rolled leftwards … The blade, striking the earth, has turned into a high steel wall which spreads and extends in an immense curve as far as the eye can see. To the left of the steel wall, on the inside of it, stands the man in metal who had charge of the guillotine. He bends and lifts up the head by its hair (snaky dark hair) and shows it to the father and mother who stand at the left … is a double face-half, the image of father’s face; half, the image of mother’s face. It is as if in this one face [is a] reflection of what in them, are two separate “people.”

In the meantime, as the guillotine falls and turns into a wall, I—kneeling now beyond the wall, for the wall begins at my neck—spring up. A new head has sprung forth upon my shoulders, it is my own, no longer the double reflection of the parents’ face. I walk away from the wall; my hair, golden and free, flying back from about me as I walk lightly away … associates free-waving hair with “my self.”

This disturbing dream seems to mark a separation from the parents’ world, but perhaps it also represented a too “intellectualized,” animus-bound attitude, which has dominated Naomi’s life.

20.7.53 Dream; N’s boat about to crash into smaller boat with child. Does know to avoid it. Crushed with a second big boat. Invisible someone takes helm from her hand and prevents crash.

“her”: not to blame myself. … final sin is of going against “her” way within oneself.

In this dream, too, there is a most dramatic turn of events. Naomi, unable to prevent crushing her inner child, is saved by an invisible someone once she yields up control. Then on July 21, she continues to dream but then comes to an important insight about her disturbed relationship with her mother in language that Neumann might have used:

I have awakened out of dream … in Japanese concentration camp … as if reading out of book … see pictures … girl cannot walk from 7–8; 12 so beautiful, made up מגונדרת now bleeding, reversed shoes … running around a room counting animals painted on the walls (like children’s paintings) … reminds me of bafflement at arithmetic at school … mother drilled me for a while each day during a holiday … torture … maps meaningless … mother drilled geography during the holiday … no connection with my life …

A sudden scrap of thought, like a fragment of an imagined conversation interrupted me just now: I was suddenly thinking of the turning outwards at puberty, of the being born “burnt” out of the Parents World. A thought voice now said: It is not being born out of the imaginary world of childhood into the normal world but a being born out of the parental ways of seeing into an attitude to outer life that corresponds to one’s inner being.

… At about puberty, an awareness of the nature of outer things seems to set in; the outer world takes on a different kind of reality, not conditioned by a child’s needs … in which everything comes to the child transformed from within according to what its needs require. The world would take on a different kind of reality, as perhaps better said, for often, seemingly), the functionings of childhood continue later (even through life, seemingly) if one or more sides of the child have not passed through the full growth to the point of being born out of the system of functioning which watches over a child’s growth.

Find myself wondering about the place of the parents and the great Parents in all this. I got confused, even as I strained to grasp what seemed to come up … out of my depth.

Earlier (June 6), Naomi had revealing dreams about her gender identity that seem connected with the traumatic memories of her autocratic, animus mother:

Dream girl turned into boy by Jesuits in childhood. Now he had to retrace his steps to … a girl and from there grow anew. And this, the dream-voice said, was the way of suffering.

Dream investigating criminal case … if it goes on much longer, I will scream. Here I tore myself awake … If lose touch with “her,” animus gets a “charge” …

The “dark men” who were originally “women” and “of her,” now come back to memory.

These two dreams illuminate key complex issues in Naomi’s inner masculine and feminine psychology. Naomi was a second girl in her family constellation. It is possible to speculate that her gender was a disappointment to her mother, who wanting a boy, rejected Naomi. When Naomi’s younger brother, Dan, was born, the affection she did not receive was given to him. Naomi compensated by developing a charged animus. The criminal investigation is about this defensive animus and the charge and the feeling of being charged.

On August 9, 1953, Naomi touches upon a basic fault: how to be in touch with her analyst without losing touch with herself:

I wonder now whether it is the renewed contact with Mrs. Jung that made me lose contact with myself—at least I feel it so now. The song אלי אלי למה עזבתני [Hebrew: My Lord, My Lord, why have you forsaken me? (Psalm 22:2)] also the refrain of a popular Israeli song has come up repeatedly. My head began to ache with the “constriction” after I left Mrs. Jung. It has grown worse this night. The paintings are getting blacker … within is darkness and harshness and despair. To judge by the paintings, there is suffering within, but I am not in contact with it. The suffering I feel is darkness not pain. I cannot go on. What is wanted of me? That I give up analysis?

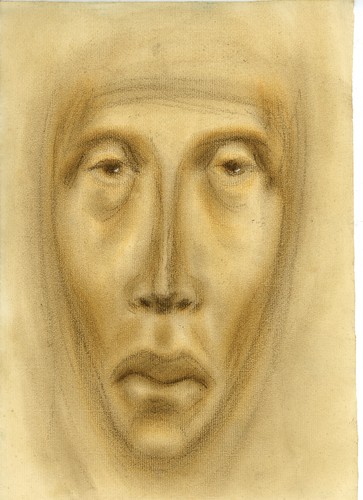

Naomi Nir, Possible self portrait

She thinks again about “dark” neglected children:

I wonder whether the neglected children (“dark” children) whom I want to adopt or take care [of in a dream], are the senses and the mind which Mrs. Jung yesterday said one must develop (the inferior functions) …

As I began [to paint], I realized what I had said to Mrs. Jung yesterday about the way colours and sounds used to fall upon me with a terrible vivid impact when I was a child. It came “from outside,” as foreign to me. I was now “saying” that it still happens to me at times even now to be “hit” like this; it is so intense that I “turn away” from the impact …

But the question is: what is the alternative way of contacting “her”? I know I lose contact with “her.” I then go in search of “her” along Jungian lines. … What is the relation of “the Jungian way” to “her”? … the question is becoming clearer and more acute …

Ambivalence lies in that it has to be accepted as belonging to … part … not to the whole …

I think I cannot survive, cannot find my relationship to this life, unless I accept pain on a different basis than the one which prompts words of friendly sympathy for this or that difficulty. It disturbs me each time Mrs. Jung says she is sorry things have been difficult, or she is sorry I didn’t sleep enough. It is the same when she asks me how I am or how I feel. The small distresses are small beside the deep anguish and cannot be mentioned as “troubles” beside it. And for the deep anguish no words of consolation can be offered, for this sphere is too deep, too near the roots of “religion” within one, to be looked upon like this. It almost bemeans what is both unendurable and great, if it becomes a matter of comforting and condolence.

The anguish is not to be spoken of—surely not to be asked about …

- who would remind me of “לקבל באהבה” [Hebrew: to accept with love] at such times, was nearer the truth.

Losing Touch

On November 30, 1953, Naomi seems to be on the edge of losing touch with reality: “Things are getting terrible. The wooden frames of my window keep looming up as a cross as it does before an agony sets in.” Naomi is inspired by reading St. John of the Cross, recalling an intense, almost ecstatic experience of flying over Spain en route to America in 1947. On the first of December, Naomi makes a significant advance and discusses her urge to protect a vulnerable child, perhaps reconnecting with her wounded inner child in a new way:

I said to Mrs. Jung today I keep recalling …

after telling her about the girl (Colette?) at the railway station that I could see how the child was being slowly damaged and I wanted to prevent this; but what could I do? …

… I keep wanting to die. I know not how to go on like this. If I die, E. will read my notes, perhaps he will come to see through them what it was I should have “brought to earth” but could not alone.

On New Year’s Eve 1954, Naomi, initially at high risk for killing herself, then has a remarkable, revitalizing epiphany:

Painted again (the tenth painting today), then dozed. I really slept, but at first kept making involuntary … movements of the left hand as soon as I began to fall asleep. Now, waking, my whole being was athrob, as though a too strong engine were at work …

The last two faces I painted brought associations of a slight frame. … and I was feeling so terrible with a too-great charge that thoughts of suicide kept coming. It seemed the only … escape. …

Today I painted all day and scarcely stand in the days to come.

Yet the last I did not consciously work through anything. But wrote. …

Also the separate halves seemed to have passed out of the picture. The right direction I thought: Everything in the picture now moves but I scarce dared believe this. I had motion (rightwards upwards) by thinking, tried to steady myself against a sudden overoptimism, how easily one steps again into darkness, how the next step leads … But the relief from the unendurable charge … [has] gone to my head, and I wanted to sing to myself because it was so good.

This evening I found myself singing, unexpectedly, Ave Maria. I have sudden memories and images of newborn infants keep coming up, in and out among quiet other thoughts and wanderings of the mind.

The melodious bells have begun … It is half past eleven.

Will they continue now for half-an hour, ringing out the chimes? Old year, ringing in the new?

…

The bells and the passing of the old year brought an intensity … A little before midnight the chiming to me, a growing excitement.

Would the ringing begin at midnight … I waited (I have never lived through this ritual). I [lie] looking at the clasp on one side of my watch, holding it in my hands. I noticed this, then forgot the watch face, above, had scratches on it.

Then returning from the wandering of my thoughts and looking at my watch. I had a sudden intense impression as though the scratches I had seen before were now an engraving … [The] clocks began to chime midnight …

At this special moment, Naomi is able to perceive meaning in random scratches on her watch face and enter, perhaps for the first time ever, fully into the present moment. Then she recalls an earlier dream:

Night after my visit to Mrs. Jung a “great dream”:

I was traveling in a kind of train or car that had benches running along each wall. I sit on one side of a bench; beside me, to my left, sits a woman (dim). We are talking. At some point a man’s voice speaks from the opposite bench, right in front of me. I can see no one there. The man explains that the physician has made him invisible … in order to be able to examine the levels of which he is made (or the order of the levels within him). To prove to me that he is really there, he says, he will hold out his hand to me across the passage. I now hold out my hand and I feel his hand, firm and solid. I realize now that he is really there, only I cannot see him … impression lying or reclining … (There is a terrible “charge” in me as I write this. There has been for some hours or so now. I can barely endure it.)

… this melody (Beethoven, Coriolanus) comes to me like a “premonition” when some great upheaval and pressure and seeming belligerence, is the “opening” that leads to something gentle and love-touched.

I still fear to speak to Mrs. J . She is his wife. I am doing a terrible thing, yet because I don’t, I sink. Guilt wreaks havoc with my “feel” of myself and simplicity. Because I cannot speak truthfully … I feel I need help—but I know not where to return.

Search for Love

On December 12, 1953, Naomi sets out what, for her, is the central conflict with analysis:

I thought now of how Jungians say: It is a part of yourself you want to accept, which you have to accept, [but] I felt were not mine but had to be worked through or … somehow discarded. Mrs. Jung spoke so …

But perhaps … it is not really part of oneself but a thing to be discarded?

… an earlier dream … This had at the time connected with Jung and his way of developing the instinctual side. This dream had come after a conversation with Mrs. June [Singer]Footnote5 where she said the instincts must be developed, and I said they were in some way what assures the human being’s functioning when awareness is lacking and that it is awareness that should be developed, not its substitute. The dream of the genius … teacher who has found a way of developing the blind so fully that they are more developed than the seeing for these have not found a genius teacher to develop their full seeing capacities and possibilities, evoked my talk with Mrs. Jung.

I connected the genius teacher of the blind, with Jung and his analysis.

… thinking yesterday of the Seminar on Children’s Dreams [Jung Citation2008], and that the one thing that does not seem to have a place in the explanations and interpretations there, is the matter of the role of love, of love damage, and of love as healing …

This touches the matter of my attitude to things Jungian.

Finally, at the end of this long entry, Naomi has a most revealing dream dilemma about forgetting and finding her glasses:

On my way there I remember I have forgotten my glasses. I ask the young woman who is my guide, if she will wait till I go back to get my glasses; it is half hour’s walk back to where I was and another half hour to return here. She now points out a pair of glasses lying on the ground nearby. I go and pick them up. But they are not mine, and I want my own. Are these the two pairs of glasses that I want to get to faced in one direction, but which don’t meet?

In a long entry on December 7, 1953, she reflects once more on the meaning of her search for love within analysis:

Walking through the streets before, I became preoccupied with this matter of there being no love in Mrs. Jung for me, and my protest against it. I thought perhaps it is a childish thing, this wish for love, something to be outgrown, something that only belongs to children.

My thoughts ran along these lines for some time, and then some change set in. I recalled what a spiritual father can mean to a troubled soul if he feels himself to be helping in the name of Christ who is love. It is not only children for whom love is healing.

Every hurt soul and all have a brokenness in them—can find healing only in love. I had imagined Mrs. Jung as expecting an adult to be more reasonable, not to be ever thirsting for love. I now thought of Miss … who is like a tree gone dry, its sap having died.

Yet somewhere in her was a tenderness which had suddenly awakened when one small child loved her and cried at her going.

… crying my heart out for the suffering and numb loneliness of so many small and tender and helpless human beings … intense pleading for help for them had broken through me. I was as if aware suddenly of “her,” and of a sea of compassion and love, of “her” suffering for the suffering of all these souls, “her” children. …

I painted then, for the intensity had become hard to endure. It seemed a poor painting at first, but when it was done, that which had come to me now began to rise as if in a flow of compassion out of the eyes and face before me. I now no longer saw the painting as I had seen it before. I saw a face of compassion, with a silent love and pain flowing out of it towards me. … swaying back and forth, too full to be contained.

The words Mater Dolorosa kept repeating themselves over and over again. When I was to look at it some hours later, I saw again the poor picture as it looks in itself bereft of the living experience. This was to happen a second time, this intense happening round a painting. Because of this intense happening I could not speak of it, and could only note (and this with great effort) after the two paintings the one word “painted.”

This face was to bring up the words … because somehow the suffering was necessary. Now the face with its pointed hood called up the painting of Heloise, the abbess,Footnote6 she who did not want to be parted from the one she loved, she who was bitter. I recalled well the bitterness which had come with that painting, how I had cried out: “I don’t want to be Heloise. I don’t want to be Heloise.” BernadetteFootnote7 was a tender girl nun who had not tasted a man’s physical love, but Heloise was a woman. And Heloise in me had not accepted, she did not want to be a nun. …

Mrs. Jung said the inner things came up in me because I had nothing to do; E. valued these things that came up under activation to such an extent that I submitted myself to them thinking that to endure the suffering of their coming and to note and record them, was the greatest thing I could give. I thought to myself that I would go on with it as long as I could endure it, then if I saw I seemed too near to going mad, I would take poison …

It is this I said in last night’s dream the writings were best destroyed and not known by humanity. The opposite view, where I was the secretary recording as exactly, as faithfully and as clearly I could all that came or appeared in this night’s dream in connection with Mrs. Jaffé who copies out for Jung (to study as I wrote for E., who could draw conclusions from the material, and heal others by means of the new insights) …

All this had come in my analysis … .

… Mrs. Jung was to ask whether E. had explained to me about transference, when I spoke of love. I said no. She said coolly that it’s a pity. That was all. That night I dreamt that I pitted love against an inhuman thing that was coming to earth (something machine like and inhuman) denied love …

The associations to this terrible [dream] were Mrs. Jung’s words about transference (implying there had been no love between E. and me); I kept feeling that Jung’s teaching had a Coptic concept of the Christian symbols death and rebirth, crucifixion and suffering and rebirth, with the element of love left out … The acceptance of suffering but without the element of love. A harsh world of disciplines, ideas, will, mortification with the human element missing, all that “she” represented and Christ, as loving, and aware of love as divine and human.

Then Mrs. Jung said I must turn away from Christ and the Queen, she said they are divine and the divine does not lead to the human.

… How could she heal by means of an analysis which activates, deliberately, these “inner ones” when she believes they do not lead to the human and one must turn away from them?

… The analysis was good. I was wicked (or just in error) to say anything against it. Yet its living effects in me were bad in her eyes, they were not meaningful, they were leading me astray. I had to turn away from them, she said. But the analysis remained good and not to be criticized. The analysis activated the not-human levels but denied love. With L. I had been spared this, I was not to see till much later the denial of love, because E. was loving and tender, and encouraged and accepted as binding all that touched upon “her” from the first. “She” dwelt in him too and was his light.

In this passage, one can feel Naomi trying to hold together the opposites, the good and the bad, the nurturing and the disappointment, in her analysis with Mrs. Jung, who had provided such a reliable container for her. In this way, perhaps she was able to hold together disparate, splintered parts of her own Self: a thinking dominated animus, a genuinely creative anima, an abandoning mother, a spirit child, a nun, a woman in love. She seems able to accept what analysis did have to offer, “analysis remained good”; even though it did not give her what she wanted: “love.” The image comes to me of a child who will not eat because the food is not what she dreamed of and so she remains unnourished. Naomi would be a most difficult patient for any analyst, yet Mrs. Jung with her calm, quiet, inner authority provided a container for at least some transformation. The fact that Mrs. Jung was a woman seems to have evoked in Naomi a conscious negative mother transference (“There is no love”) but also an unconscious attachment that did allow for some healing.

Resisting and Turning Against Jung

Naomi was deeply drawn to Jungian psychology but also profoundly repelled by it. The inner turmoil that analysis brings up in Naomi is expressed in terms of “charge” and “activation” that overwhelms her. Here is a rather typical passage:

Fear of “activation” (= triggers?) that has always come through analysis, the “fire” which seemed ever to take me away from love. “Fire” to me is still the great danger. My resistance to it is weak; my bones are of “celluloid,” as I was told in a dream some years ago.

Throughout this year, Naomi experiences “love” and “analysis” in opposition to each other, saying over and over, that “love” is lacking in Jungian psychology. Repeatedly, Naomi stresses the inability to give herself over to the analytical relationship because of her resistance to Jung’s ideas:

I cannot befriend Mrs. Jung—knowing this—for perhaps in being good to me and befriending me, she is now tending a snake. “This is what it seems to lose one’s innocence. I cannot accept her friendliness now when I have these thoughts of “changing” things, of “going against Jung” as Dr. B wanted me to do.Footnote8 I thought of Dr. B. now with hatred almost, with despair, because he had encouraged my “fighting” against Jung.” Now it seems that I could only accept their friendship if I could “unknow”—lose all knowledge of—the dark task which Dr. B. has as-it-were imposed on me by making the negative, “fighting, prophesying,” side in me seem like the bearer of healing to humanity, healing and freedom …

Ah God! These days of conflict, when all this burst into consciousness, I did not know if he was my enemy or my friend. …

Jung’s spiritual greatness, I felt dimly a longing to “accept” him, to cease fighting him … If I could accept him in my heart, my longing for friendship with Mrs. Jung, with Jung … would not bring this feeling of “false pretense,” or pretended friendship.

I thought today: “Perhaps if I cease going against my way, I will no longer have to fight.”

Naomi’s torment makes it most difficult for her to reflect on her resistance to Mrs. Jung as a projection of an “authority transference.” Indeed, she feels she must hide her thoughts from her.

How could I go to Mrs. Jung now in friendship as I had done—now that all thus has reached my awareness?

… I thought: “I will not go, then, I cannot.” I felt I could not tell her these things; nor could I go pretending to be simply and innocently telling the truth and being friendly, when all this was no longer covered up by forgetfulness as it had been. I felt I must stay alone til I know where I stand. If Dr. B.’s “plan” for me here was false, I would discard it and then see what the next step is. Perhaps I could then once more give my friendship candidly and receive Mrs. Jung’s friendship in frank untroubled acceptance. If my way should prove to be in some way “against” Jung, I could not go to her at all (or I could not go unless I made my position clear to her?).

I decided I would not go. That was on Sunday.

Naomi is unable to break off the analysis but is unable to truly enter into it. Nor is she able to reflect on her ambivalence. Naomi’s inner conflict intensifies:

Gradually—as the animosity against her had begun “to take on meaning”—the matter of going to Mrs. Jung and not admitting my “fighting against Jung,” came up. This was the “lie” I was proposing to live. This was one of the problems which made my going to Mrs. Jung a horror to me—acting on me like an illness when I was not aware of it, and also when I was aware of it as unendurable situation.

Naomi continues to express her ongoing, deep ambivalence to analysis:

… it was a bad thing that I did when I told Mrs. Jung about my doubts concerning analytical psychology. I had fought all the time against saying anything hurtful and “unaware” of the life of others—I felt it would not be “of ‘her’”—but I lost the battle in the end. I feel I may not “say everything” although the way of the analysis not only accepts but demands this. I felt I must hold on to my awareness of “her” in me all the time, step by step. But I am lost in the end. And the “activation” had become too strong.

Some dim (“deep”) feeling that I should make amends, has come. I know not how yet.

In this passage, Naomi is acutely aware of her conflict that is undermining the analysis. She understands she should speak openly about everything. But if she is critical of Jungian psychology, she feels bad, judged, followed by an agonizing need to make amends. It is as if she comes to confession asking for forgiveness but insists on telling the priest she does not believe in the Trinity or forgiveness. She continues what might be seen as a “persona anxiety” but actually reflects a deeper longing to belong:

Then, as the question became more disturbing, I began to feel I must be the thief, that I am somehow dishonest … “But I am student [at Jung institute] under false pretenses—I take only one lecture.”

A dishonesty within me acts like a disrupting thing within me, an irritant I cannot contain. I kept recalling how “innocent” I felt when I first came here, when I first went to Mrs. Jung. I seem to have been then at a childlike “place” where an awareness of the problem would come up. I recall now, with pain and longing, that feeling of innocence; I recalled that innocence in the faces I painted; I recall the words נקי כפים ובר לבב [Hebrew: “clean of hands and pure of heart”].Footnote9

That came once when I washed my hands.

Now then have I become so impure?

On the following day June 7, 1953, Naomi writes upon awakening, following a difficult visit to Mrs. Jung:

How can Mrs. Jung like me, or feel warm towards me? … I am kind of a living rebuke to her because through the analysis I have become so detached from life, and she realizes this … Can I feel warm towards her, in a simple sincere way, when I feel guilty for bringing up my doubts to her? … What should I do? Cease going? Try to work through things alone? Using Jung’s book when such contact or “activation” seems needed? What is the answer?

I had told her previously, hesitantly, about the “ritual” of the Queen’s coronation.Footnote10 Yesterday Mrs. Jung said this does not lead to the earth; … more attention to my “outer realities” in the past and present … inner things are divine and not human and I should try for human …

Then dramatically, on June 12, Naomi agrees to follow Mrs. Jung’s guidance to come down to earth:

I said to Mrs. Jung: I am coming to earth, but it must be slowly from within … the matter of working with children has come up …

- who spoke of the “Spiritual Ecclesia” and valued it … to sacrifice one’s earthly life—E. was nearer to the truth.

Yet Mrs. Jung has evaluated things according to her woman-nature—earthly life comes first. If there is need of choice—E. would choose the “Spiritual Ecclesia,” she would choose “normal life.” Both express the deep bias in their very nature as man and woman, in their very being.

… Mrs. Jung has nothing of the mystic in her—and no understanding … my heart will break, that to seek “her” alone … is too much for me alone. … Why should he [E.] refuse his friendship? We could be soul-companions … I ask no more than that. Soul-companions …

On the very next day, July 13, Naomi is tormented once more:

… I must not speak of “her” … “fighting” … You said I must turn away from Christ and the things connected with “the Queen,” because they are of the divine and the divine does not lead to the human [as if saying]: “Turn away from God—because God is divine.”

Then in an entry on August 11, she is once more searching for her place in the “Jungian Way”:

… I am seeking for the place of the “Jungian Way” in the scheme of things. Ah, God, I am seeking to accept him, not to reject. I know that “way” holds healing. To find what is gold there and separate it from the dross!

Ah, God! The dream of the woman who had “stick” that showed where gold (or water) was buried. Yet the activation was to damage my contact with “her” again and again. Indeed, it was as I said (how painfully the realization reached me!) that in my experience of the analysis I had come near to “her,” and in that same analysis and what it brought I had been damaged and the contact with “her” too, and I was led further and further from “her” and Jungian teaching as it stands does not know enough about the things it works with, the forces it touches and activates, to tell what leads to “her” and what leads away. Somewhere in my experience of the analysis the clues lay to these things. The record had been kept so fully from a certain point onwards. There is needed the eye to see and understand that which is written.

How can we understand the attraction-repulsion dynamics of Naomi toward Jungian psychology and Mrs. Jung? On the one hand, for someone like Naomi who had an intense spiritual life, Jungian analysis was probably an appropriate choice. On the other hand, her thinking function and critical animus seemed to block any real emotional relationship with Mrs. Jung. Underlying it all, was a powerful Great Mother transference that demanded love, instead of reflection and integration.

Naomi and Her “Inner Neumann”

On May 13, 1953, she writes very nostalgically about her relationship with Erich Neumann: “He knew all of my inner life, and yet he came then to see as though to be normal were more than that … seeing these things as not meaningful, continued to haunt me.” Then the following week, on May 21, she writes one of her many, unsent, but poignant, letters to Neumann:

It seems as if I must write “to you,” that this “record” must be written for you.

I said recently to Mrs. Jung that I don’t know what I write for, that I used to write feeling it was for you, that after I ceased being able to give you the writings I couldn’t write. (I was remembering the terrible months after you left for Switzerland in 1952, and when I gradually became unable to write—until I saw you again early in December, when I came to you and you said you had no time for me and we only exchanged a few poor words. After that I could write, “to you” again. I do not understand the nature of my bond with you but it is so real to me that if I lose the feeling of it, I die.)

Then two days later, on May 23, a moment of solace and then another letter:

It is early morning, E. and the birds are calling sweet musical calls … how they understand each other when they all seem to be talking at once …

Dear E., such troubling things have been coming up. I wish you were here, as in the days when you were my friend and reassured me when I became anxious. … very troubled I painted. And now it is done and the things that came up with it have troubled me deeply. I painted a “face of pain,” in browns and umbers. And as I painted (I find it hard to write it).

Her intense engagement with the inner Neumann continues in a dream recorded the following day:

Dream: inner one came to my room to talk to me and help me, but I suddenly remembered my room was not fittingly tidy, and when I got up to tidy it (or when this thought came?) “he” disappeared … followed by being a group of girls but isolated, “uncooperative.” Something prevents me from joining them.

In the next scene, I am with E. I tell him the two dreams (apparently) and I end by saying—referring to the “one” who comes to my room each morning—“I will not be able to cooperate for a week (Or two weeks?) for inner reasons.”

Her inner dialogue with Neumann continues both within the dream and without, reflecting a high level of reflectiveness. But she also highlights issues around “persona”—“when I got up to tidy [my room], ‘he’ disappeared.” She also reflects the great difficulty of allowing outer and even inner figures into her inner space because “I will not be able to cooperate.” When she is “charged,” there is no shared space where the inner part of herself can meet.

Soon after, her ongoing, deep ambivalence toward the act of writing is expressed: “ … told not to write what ‘she’ says to me. I recalled repeatedly yesterday how ‘she’ had told me these things are ‘to be lived, not written.’” Normally Naomi experiences a clash between “she” and Mrs. Jung, but in this case, the attitude of “she” corresponds directly to that of Mrs. Jung who is also struggling to get Naomi to enter, and be, in life. At the end of the day’s entry she adds: “I recalled how I had told this to E., who had said, slowly: ‘What a thing to say to me!’”

Throughout most of the analysis with Mrs. Jung, Naomi was painting intensively. It was for her a form of art therapy, which often allowed her to go deeper than words could take her, perhaps similar to Jung’s confrontation with the unconscious as recorded in The Red Book. On May 25, 1953, Naomi continues her inner dialogue with Neumann starting with a striking image:

To E. Painted mask of pain and pain went away …

I felt I must not blame myself; it was too much for me, what I have been living.

Face recalled, “crucified ape” I painted years ago … this tormented one, without grace, to whom all these happenings are only suffering, without light, only torture, not life. Darkness of face filled me with dismay. “Who is this ‘one’?” I kept asking within, anxiously.

… all darkness, all sin, without meaning … only suffering, and the horror of what he had done.

The painting of a mask of pain brings Naomi emotional relief and may be seen as a creative kind of art therapy, done alone, without the art therapist. The tormenting image of a “crucified ape” recalls Neumann’s own dream of the apeman that inspired him to write Depth Psychology and a New Ethic that he described in a June 14, 1957, letter to Jung (Liebscher Citation2015, 113 N, 331). Otherwise, she is struggling with “suffering, without light, only torture, not life” unable to find her place in life.

On the following day, May 26, 1953, she describes an intense, seemingly erotic dream with Neumann:

Dear E.

… The dream where you kissed my lips, and as you did so the “false arms” fell away and I raised my face which had been hidden by them …

This dream does not seem to express an erotic desire for her “analyst-lover,” but rather the symbolic possibility for transformation. Once Naomi receives pure love from her inner Neumann, a loving animus or inner lover, then her defenses, those “false arms,” will fall away and her authentic self will be revealed. Significantly, this is the first positive dream Naomi recorded in 1953. Despite her continuing critique of Mrs. Jung, it very likely reflected the progress of their work together.

Naomi’s dream on the next night (May 27) reflects even more poignantly the possibility of a “new start”: “Dear E, last night’s dreams … jewel in new setting.” Then in her journal suddenly she reveals why she had visited Küsnacht, as mentioned in Part One. It had a special, tragic meaning: “My grandfather’s grief at dying here in Switzerland comes up (He died in Küsnacht in the house of Dr. Brunner). He cried like a child, saying that he was dying without returning first to Israel.” Küsnacht has the symbolism of being a place of death, a “lost homecoming” and a journey never finished.

On June 11, she recalls the erotic tensions in analysis with E.:

It was said for me. It seems I may not touch you—that I must be to you what Joseph was to Maria. I recalled the severe depression that came to me then, lasting for weeks.

… that one must withdraw from life and live alone, apart.

I recall, I was again (these last days) “fighting” over E’s saying that I had no place in normal life, that I belonged to the “spiritual ecclesia.”

17.6.53

Dear E., I cannot understand what is happening.

I have painted a Yemenite head suddenly. As I painted, the song of early morn—Grieg’s “Au Matin”—sang softly in me, over and over. And yet the “Yemenites” have ever represented to me something gone dark and destructive, “mysticism” gone very negative.

As I painted I kept “saying” to Mrs. Jung in imagination; “The Yemenites have the most delicate faces among all the “races” of the Jews. …

After painted the child with pain in its face, I began to “feel fine” …

When I began to paint (“to pain”), I thought I would paint a child—but it did not come. Instead this head came up, recalling “Queen Shub-Ad,” the Mother-figure who is dying and with her there is the danger of the “musicians” being buried too … .

Wondered … further from pain or was I being led around to it? Wanted to stop in middle, then painted Yemenite …

I thought suddenly, as I recalled this: “it is not the ‘one’ who is in contact with ‘her’ who must go to the analysis, but the ‘ones’ within who are of the ‘Parents’ world.’” I recalled what I had written yesterday (and not sent) about my experience being that the analysis is the “place” where the errors are cast up, one’s own errors and errors of the age …

As if analysis should be the “place” where one contacted “her.”

I also recalled what it meant to me that in the analysis with E., I had learned to contact “her.” I tried to think out these two seeming-opposites, but became confused.

23.6.53

I am not sure where I am to-day … as if I were somehow “hovering” over something, unable to settle.

- haunts me. Dim awareness of him as bound up with the “Flammentod,” are about me.

The moth and “Flammentod” [death by burning] are so close, their breaths brush past me.

… I dreamt of E. last night.

Who loved deeply in his inner life yet did not withdraw from the world.

… why am I so loveless and insensitive, when I would be loving and understanding above all else? … I have to learn to be silent … not to say everything.

At such times, I see myself as all-shadow, all-darkness. To whom do I bring light or love or goodness? Where in my life do I give “place” and “form” to all that my awareness of “her” has meant to me … I have suddenly awakened into a moment of too-great “charge” … almost terror … What am I to do? What is to become of me? …

E., my dear one, where are you?

7.7.53

I have suddenly awakened into a moment of too-great “charge” … almost terror … What am I to do? What is to become of me? …

E., my dear one, where are you?

Later at home, I wondered whether I would not have found my way earlier in life if I had not broken and entered the great darkness when you turned against me.

I was “nearing the earth” then, and this was the problem then—to distinguish between “her” earthliness and the “mother’s” earthliness.

The problem became too much for us both then, and things became dark. But I seem to be nearing now what was trying to work itself out then before the darkness came.

To cope with these things with you against me, was beyond what I could do. I was so deeply attached to you, you were so deeply woven into the deep things in my life. Look, even now, what a place the feeling of a “bond” with you, has in my life.

I wonder at times what I am now within you. As the darkness has slowly passed away from what was between us, the light has remained … I think peace would come to me if I knew that in you too the light that was in our friendship has remained.

11.8.53

… question of the struggle with “Jungian things” without going through the question of the split … I have wondered whether “Jung’s world” got fixed in the “split” in me somehow.

… the earliest clear dream of a “split” … came soon after I ceased going to E. for analysis (if not before).

I dreamt I was in my grandmother Rachel’s flat (… we lived downstairs …) I stood on a balcony looking at the sky. Something like an immense arrow was falling from the sky. It was red hot, one could see the very heat of it all about it. [She] recalls Graf Zeppelin … years before … crashed into house … embedding itself in the ground; then it bent down and cut the house into two.

I knew my brother was downstairs in his room trapped there facing the red-hot arrow … for two days and two nights. Then … leave and then the house would collapse. I wanted to run to my brother, that he should not be alone there. But as I reached downstairs (I had been upstairs) stones crashed down in my path from upstairs (?). I understood I was being prevented from going to my brother. Was “she” preventing it? Was it “her” wish? My grandmother seemed to represent “her” in dreams.

When I told E. of this dream one day, he said it was impossible, one does not leave the Parents’ world.

I recall, I felt after this dream, that the world of the Archetypes is built over the world of childhood (the second story where the Great Parents lived, built over my childhood).

I thought today that in E. “she” was such a reality because there was so much love in him.

25.11.53

- could see the significance of negative seeming reactions and resistances where Mrs. Jung … cannot. If there is love in a Jungian (as in E., or, I believe, in Jung, though I don’t know him) it is because it is there. It does not enter into the picture of the psyche, into the system of explanations, of causes and effects and the functioning within the psyche. I thought today that in E. “she” was such a reality because there was so much love in him.

It is this quality of love, of tenderness, quick sensitive sympathy that has to be developed that has not found its genius teacher yet who would turn a visionary eye upon the inner place of love and its functioning in the human soul and inhuman life as Jung did for so much else in the psyche. Another who would find a way to recontact this love and tend its unfolding, learn the laws of its growth, the ways it is damaged and how to heal the damage.

- could have been such a teacher. Will he come to it to find his way beyond what he received from his own great teacher?

The face of human life would change if such a teacher rose.

Perhaps this was not the way intended for the mystical love child in me, but had somehow been imposed on me by E.?

… E.’s grace as lying in his being a tender adult, one so near love and a compassionate understanding.

This image of Neumann as “one so near love and a compassionate understanding” is the last mention of Neumann in Naomi’s Notes for 1953 and has a tender, healing tone. It shows that Naomi was able to connect with a stable, loving inner figure who could understand her and it was certainly the result of her analysis with Mrs. Jung.

What is striking in Naomi’s memories, dreams, and reflections about Neumann is how much she seems in dialogue with her “inner Neumann” and with real emotional freedom. So many archetypes come into play: the passionate lover, the mystical lover, the abandoned lover, the artist, the student, the mystical child, and more. Despite the “charge” and confusion, gradually an inner clarity emerges. She must renounce her erotic desires for Neumann and become like Mary to Joseph in the Gospels. The archetype of the Great Parents is built over her child. Neumann is a fount of love and understanding, deeply inner, but not turned away from the world. He becomes the role model-teacher she has been seeking, saying “there was so much love in him.”

Through this dialogue with her inner Neumann, she comes to an edifying realization that it is her task to be aware of “she” even when other people are not. Here, one might say, using Neumann’s own master metaphor, she has activated, not another “complex,” but a dynamic ego-Self axis. In a metaphorical way, we might say that Naomi had two analyses with Neumann: one in 1949 in person in Tel Aviv, and another virtual, inner analysis, co-existing with her analysis with Mrs. Jung. In the early days of Jungian analysis, it was not unusual for people to undergo two simultaneous analyses, one with a man and one with a woman. Although such multiple analysesFootnote11 are long out of favor, perhaps it is exactly what Naomi needed to heal her animus, allow her anima to flower, and not lose touch with her most important inner voice, “she.”

Reading Jung

Naomi was deeply affected when reading Jung or books on analytical psychology. This emotional intensity predates her analysis with Mrs. Jung. In a letter from Neumann to Naomi on March 9, 1952, Neumann tries to help Naomi be reflective about her criticism of Jung and analytical psychology:

First. Don’t argue against Jung, argue against me. Second. There was not a Jungian analysis. Remember, I let you go your own way, right or wrong as it was. You would not accept your animus-position was yet too strong, then you ran away, right or wrong as it was, and there was our latent and manifest personal connection in it. From an analytical standpoint I was a failure, if from the standpoint of your life too. The gods have to decide. But therefore you are not in a condition to argue against analysis and against Jung … All your argumentation is animus—argumentation and not “She” … I don’t believe there is a way, there is only to try … But love should teach you, not to condemn the erroneous ways of others …

In early April 1953, Naomi is strongly triggered by the idea that she might be one of those cases in which analysis should not be used:

I had read on in Jacobi’s book through one long troubled day, reading off-and-on. And so I came to read Jung’s word about the cases when this type of analysis should not be used. I cannot talk of it even now. The trouble it woke in me was too terrible, too near chaos. The very thought of it still seems to darken my mind.

On June 25, 1953, she describes the profound impact of reading Jung’s books:

It is near two o’clock. I would go to sleep if had the peace. …

I took up Jung’s book bought to-day … disturbs, fascinating … “warning” and dim distress … as I read the first few pages of Jung’s forward (written in 1950) about how book came to him overwhelmingly, like an explosion of all psychic contents which Freud’s view could not hold—some dim thought of my struggles with “Jung’s world” because of contents it seems to have no place for me, came up.

On the following day, June 26, reading Jung triggers feelings of guilt with Mrs. Jung and then yearning for merging with Jung and his writings:

I had doubts whether it was really “allowed” that I read it … Holds back to tell Mrs. Jung … Reading book last night, I longed to accept everything in it, not to struggle or strive against things in it. I wanted gradually to read all of his works, to make his world my own. Of all that I have met, this “world” lies nearest to me.

Toward the end of the year (December 4), she returns again to her emotional experience of reading Jung:

I read Jung’s book but whether I projected [feelings] or they are there I do not know. But at times one had the feeling that he saw Miss Miller’s preoccupation with religion, and the moth and the sun, … as a regression … an unfulfilled desire for the handsome ship’s officer. His use of the words religious regression disturbed me not a little. Later he takes up the myths of the sun and religious mysteries and transformations, and treats them grandly but I felt the two attitudes didn’t meet.

Again, toward the end of the year, on December 30, 1953, Naomi is tormented by reading Jung:

What is happening is horrible. Why then was it necessary for me to [torment my] self by reading Jung’s book? … I realized … Jung’s way could have helped her … I should not turn against Jung or undervalue him? … (I write this hesitantly, this may be state in all who come to him) …

Four years later, on March 16, 1957, Naomi is still immersed in her intensified experience of reading Jung, but now comes to some sort of resolution, even working through her critique of his psychology:

Reading in Jung’s “Symbols of Transformation.” Thought dimly of the fact that I have not found it necessary to comment on things Jung says, though the book shows again and again the poverty of the side in him that could be aware of the reality of the world of love and the “inner experiences” bound up with it. The poverty is marked, again and again, but I have no longer had any need to comment. I thought last night: “Did I need to write it only so long as E. was held by Jung’s attitude to love? For the writings were bound up with E. Now that E. is no longer held by Jung’s views where “Love” goes, there is no need for me to write against these views …

I also recalled now that on the way to the Home (where Naomi worked)—a piece of barren rocky ground—there is, in fact, little that is living, little that grows. What I stop to listen to and watch, is the silence, the view of sky and mountains, in which I seek reminders of the Companion; I try to recollect myself before I must enter the Home where I seem so often to lose my inner awareness.

… What is strange, however, in my walking alone? Is it the way I lose awareness of the Companion when I go to work that is strange? It is the final loneliness to walk without the Companion.

… painting makes me unable to use my “hands” some other (some love-way)—that makes me unable to move into a larger “inner room” …

- who had a living awareness of “her” … a living problem, in his life—he was aware of it and could realize it was built on a “split” … damage can come through lovelessness or lack of love.

Again and again, Naomi struggled to find her task in life and whether writing her journals was worthwhile or not. Naomi did feel, during her time in analysis with Mrs. Jung, that she had a vocation as a translator: “the task she feels assigned to her.” In keeping with her view of her life as spirit, “the language of the writer doesn’t matter, what matters is the essence of it.” Indeed, she may have had a special sensitivity to language. In reading English translations of Neumann’s work, she is “put off by the English, doubts he would have said particular thing and therefore checks against the German—and sees that the translator has indeed added things not in the original that change the tone.” In the end, Naomi was able to a certain extent to realize her “vocation” as “another human being [bringing] something of this compassion and love” to children, despite being herself “so imperfect a vessel.”

The “love” she sought but did not find in analysis, she may have found through Christian mystics especially St. John of the Cross, which Mrs. Jung had given her to read. Naomi calls St. John of the Cross, “the greatest psychologist I have ever met,” greater even than Neumann.

While reading the copy of that book, she realizes that the markings must be Jung’s, but they stop at the chapter, “On the Need to Get beyond Sense Impression” and only resume 150 pages later. As a result, she critically believes that Jung missed the most important part. He could have been Jung’s master, she adds. Naomi then imagines a talk with her eldest daughter, now age ten. Explaining why she left them as children and says only “because I am solitary.”

On August 8, 1953, she recalls intense musical experiences from childhood and from early days of being a mother:

At some point this night I realized how in childhood I would squirm with a kind of feeling of being tortured in ecstasy when my mother played the piano. I recall Ofra [Jennifer] as a baby in her pram—how she would begin to lift up her stomach (pressing herself on her head and shoulders and little feet) when I sang to her. It seemed to drive her beside herself, and I finally decided not to do after “showing it off” to someone. She reacted to this singing as to something “too much,” a kind of ecstatic-torture. I was like that when a child as early as I can remember. And the “mystical experiences” that first clearly came to me as “overwhelming” and a “loss of consciousness” from which one “returns”—happened when I heard music, once at a film, at a cinema open to the starry sky, and once at a concert hall.

… excluded “inner things” overwhelm intensity … but not if lovingly, growing to receive them as one developed.

Then two days later, she notes how painting has a soothing effect on itching or pains in the bone:

… dreams of inner writing … Only painting would still the trouble during the waking hours …

… an itching that drove me wild, on the skin of the stomach and back. This could be stopped at once by painting, often by writing. The charged “pains in the bones” … always directly connected with inner things. These pains too could be stopped by moving out of the “place” one was in, in one way or another.

… afternoon when I lay on my bed driven wild by the ringing “music” which alternated with the in “ringing music” came with terrible “pains in the bones” … so agonizing and so near ecstasy …

I recalled E.’s words: “Impregnation through suffering” when I told him of this impression of “immense ‘guardian angel’ [thrusting] his spear through me from the back, at the left,” but now I was unsure whether he said “impregnation through love” or “impregnation through suffering.”

This important entry gives a rare glimpse of Naomi’s psychoid level as the inner source of the psychosomatic pain and discomfort that were “always connected to inner things” and had brought her to analysis with Mrs. Jung. She was, as Neumann (and the Christian mystics) said, “impregnated through suffering.” Painting, or sometimes writing, provided healing. Music, at this time was also intensely two sided. It drove her wild, bringing agonizing “pains in the bones,” but also ecstasy.

Return to Israel

At the end of analysis, Naomi returned to Israel. At first, she found work at an archaeological site, restoring broken pottery. In this work, guided by her sensation function, she was able to reconstruct fragments and splinters of clay into whole vessels. On the symbolic level, this careful, patient work allowed her to gather together fragments and splinters within her shattered psyche and create a new, good-enough inner vessel.

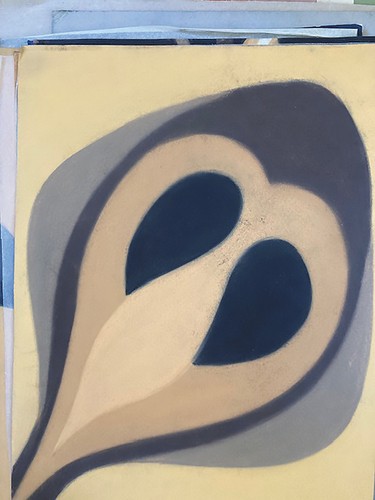

Naomi Nir, Connections

Later, Naomi was able to build on her training in Switzerland and began working as a play-art therapist in a residential institution for disturbed children in Jerusalem. Naomi, in working with these outer children, was able in some ways to continue healing her inner child and to perhaps emerge as a wounded healer. In a 1957 letter to Erich Neumann, she describes her work at the children’s home. She even gives an interesting case account of one of her patients:

Dear E.,

I did not tell you in any of my letters that I work with children. I work at a home for problem children, mainly play therapy …