IAAP congress Kyoto 2016

Introduction

Allow me to begin with a spoiler, psychotic people do dream. Many of them can relate dreams, and their dreams are not extraordinary. Moreover, conducting the project that we are going to discuss with you we were amazed to find out how impossible it is sometimes to discern between dreams of psychotic hospitalized patients and the dreams of non-psychotics, those dreams we all have, or hear in our consulting rooms analyzing our "normal" neurotic patients. Yet some psychotic patients could not tell their dreams, and not because they did not want to share them with the others in the group process we are going to describe.

Our endeavor to understand whether psychotics have dreams began with the understanding that this question was not an obvious one.

Brain neuronal dreaming activity is universal as we know; it is recorded in mammals, in the embryonic stage and so, why should it not exist in psychotics. A pioneering article published on "Nature", Aug 2015 shows cortical activity in dreaming periods, i.e. during REM periods, as identical with the cortical activity recorded while the brain is stimulated by regular visual stimuli while awake.1 The meaning of that would be that dreaming activity might have the same intensity and be perceived as real as the external stimuli we are all exposed to while awake.

But are brain neuronal dreaming activity and the capacity to relate dreams similar phenomena?

As analytical psychologists, following Jung's legacy, we understand dreams as an autonomous product of the unconscious, bearing a complementary and compensatory role on consciousness. On these grounds, for a dream to be perceived as such, a well differentiated and functioning ego is required. In other words, there is a need in the psyche for a structure capable of intercepting and perceiving the symbols arising from the unconscious as an experience different from daily awakeness experience. The existence of an internal duality seems necessary in order to permit a dialogue from which the narrative of the dream stems, often (but not always) giving to it a personal meaning.

Psychosis, on the other hand, is understood and defined as a state in which consciousness is overwhelmed by products of the unconscious. It is as if an internal barrier collapses, and elements of the personal and collective unconscious flood consciousness, coming to direct contact with the external world. In psychosis the ability to discern an internal state from an external one is lost.

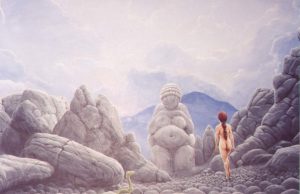

For Jung psychosis is parallel to a dream without sleep. It is as if the dreamer is "normally psychotic" and the psychotic is "normally dreaming".

On these grounds psychosis and dreaming appear to be mutually exclusive phenomena. In other words, we asked ourselves if psychosis and dreaming can coexist, and if they do, what meaning could this have for the clinician who is trying to grasp the psychotic experience, to treat and maybe to cure psychotic disease.

Furthermore, we asked ourselves whether the capacity to discern between these two experiences – going through an acute psychosis and telling a dream – marks the limit between madness and sanity. We asked ourselves if it was possible that the ability to narrate a dream was the first sign of a remitting psychosis. Maybe the most important question is whether the effort per se to mark the limit between the psychotic experience and the dreaming experience is a therapeutic tool?

Last we asked: Are dream contents related by psychotics closer to collective materials, and can psychosis be looked upon therefore as a bridge to "Anima Mundi"? Jung himself was ambivalent on this issue, in 1939 in his article "On the Psychogenesis of Schizophrenia" he claims the "abaissement" of the mental level (i.e. the weakness of the ego) in schizophrenia is such as never encountered in neurotic condition producing therefore a wealth of collective material.2 In continuation he claims that the symptomatology of schizophrenia is a mixture of collective and personal material, but that the collective material seems to predominate as is the case in those "big dreams" encountered on the crossroads of our existence. It would be logical therefore to expect collective material to predominate in the dreams of schizophrenic patients. On the other hand on a later article named "Schizophrenia" published in 1957 he claims that "….it would be difficult to distinguish most dreams of schizophrenics from those of normal people".

We believe our endeavor to look into the dreams of psychotic patients is just a first step, and we did not find previous works on this subject.

Setup

This study was conducted in an acute psychiatric ward, one of the eight departments of the Beer Yaakov Mental Health Center. It has 34 beds and is separated into an open and a locked wing. Admitted patients suffer from different acute psychiatric disorders: psychotic states, affective disorders and decompensated personality disorders. We also have to deal with forensic cases. The staff is multidisciplinary and includes psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, occupational, art and dance therapy specialists. We use individual and group therapy. Emphasis is put on milieu therapy and on group processes. Every patient is invited to participate in at least two group activities every day. It is understood that we believe group therapy to be a powerful tool in our armamentarium.

Initially, the decision to initiate a group dealing with dreams for psychotic patients caused concern among the staff: we could not predict the results of this initiative. We were worried that dealing with unconscious material could worsen the psychotic symptoms, especially as our patients suffer from a fragile or hardly existing reality testing. Until then, most of our group activities were focused on rehabilitation targets aiming to strengthen defense mechanisms and ego functioning.

Nevertheless, we were surprised with the good cooperation of the majority of patients. Moreover, they were impressed by the unusual topic of this group. One of the patients said: “I can hardly believe that psychiatrists can be interested in our dreams.” This feedback stimulated us to continue.

The group setting: an open set group, once a week, at the same hour, at the same room, half an hour sessions with two facilitators. We opened every session by encouraging the participants to share their dreams because we believe dreams to have a significant role in our psyche. We recorded the dreams without giving any comments or judgment but encouraged associations whenever possible.

Results

The study group consisted of 63 patients (34 men and 29 women, age 19 – 65 years). Ninety six dreams were recorded: 34 dreams had a personal content and 62 ones had a collective content.

We have recognized two types of dreams:

The first type were those dreams that were perceived as dreams clearly different from reality, they had a structure and a scenario.

An example of this type is a dream of a female patient in her forties who suffered from a transient psychosis probably as sign of a decompensated personality disorder:

“I was dreaming that I approach the nurse Tikva (the meaning of this name is Hope). I tell her that I think something is wrong with my treatment. I ask her to clarify it with Dr. Yakirevitch (my doctor). Then I see soapy fluid dripping from a soapbox or maybe a test tube. The fluid looks spoilt. I got scared. Something is wrong with my treatment. The color is bad.”

This patient was able to distinguish her dream from her daily reality and also to share associations. Following this dream she asked herself whether her treatment was right or wrong. This idea continued to be discussed later during individual sessions.

We noticed that the patients who could share their dreams and related emotions had a benign course: their psychotic symptoms faded rapidly and their reality testing improved quicker.

The second type of dreams was observed in patients with acute or chronic psychosis with decreased ability to separate between dreams and reality.

Here are some narratives of a female patient in her thirties suffering from an acute hallucinatory state. A few days prior to her admission she kicked her mother away from home claiming that her mother was the devil.

“I was dreaming that the voice of God is speaking to me. I know this is God. I was dreaming that the voice told me to throw away from home all meat products I was keeping in my fridge. If I didn't, something bad will happen to my son”.

The patient could not share associations to the dream, but days earlier, just before she was admitted to the hospital, she threw out of the window the contents of her fridge.

Another example of her dream:

“I saw the dream saying through my mom that I have sold myself. I had sinned when I bought expensive garments. My mom says it to me in my dream."

And the second one: “I was dreaming that there are many sins in parents’ house and when the end of the world comes they will not survive. When my mom came home I had to send her away because she was a Devil”.

Both these dreams were identical to her psychotic content. She accepted the meaning of the dreams very literally and behaved according to their content.

Another example is of 30-years-old woman patient with paranoid ideas.

“While sleeping I feel terrors, tension and a gaze staring at me out of the dream. Somebody is looking at me from outside, and I don’t see him.”

It was impossible here to understand whether she reported dreams, thoughts or real events.

Dreams of this type were sometimes bizarre. Such is the dream of a chronic schizophrenic man patient in his fifties. “I saw in my dream that I had two babies that looked like fish. I was laughing and crying”.

Fifteen out of 96 collected dreams had religious contents, sometimes very concrete:

“I am the God”.

“I saw God not once and not twice. He has a nose, a mouth, and eyes. He said that there will be a huge earth quake”.

In all these latter examples the dreamers could not discern their dreaming experiences from their psychotic contents experienced while awake.

Our additional observation was the evolving dreams: a series of dreams presented by patients who participated in the group meetings regularly and contributed their dreams continuously. It is interesting to observe the process taking place in the unconscious as parallel to the improving clinical conditions of the dreamer.

A schizophrenic woman in her thirties:

"There was a ship, and all the people on it were ill because of an epidemic. I was there trying not to get infected. I climbed on the deck of the ship and reached the steering wheel and decided to steer the ship towards the coast that was just one kilometer away. I did not succeed to stop the ship when I approached the shore. A gate separating the sea and the land had broken. 100 meters afterwards there was another gate that had broken down as well. I woke up when the gate broke and the earth was flooded by the sea."

"I wanted to be with (not clear whether the meaning is "to be in a relationship" or "to make love") with a man from my work place but when the moment came, when we were together and it was possible, he said that I disgusted him, and I felt very offended".

"I return to work. It’s my first day in the office, and everything is different. I decide to uninstall windows on my computer and to install Dos instead. It is too difficult. I decide to quit this agency and to go to another office, a competing one. I go there on foot. There is another manager. He says that he is the "content manager". I tell him that I am experienced in "flash programs" and not in the content, and he says that both things go together. I think that it is strange and I feel that I have not arrived at the right place for me."

Here the patient shows the internal movement from collective frightening themes to a more personal approach, dealing through the dreams with actual personal problems.

One more example: a young man in his twenties, acutely psychotic and on the first admission to a psychiatric ward:

“I dream seeing Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai (known by his acronym Rashbi, a 2nd-century sage in ancient Israel believed to have had holy magic powers)”.

"I was dreaming that somebody was killing my Dad or maybe Rabbi Ovadia Yosef” (a Talmudic scholar and an admired spiritual leader of one of Israel's orthodox parties, still alive at the time of the dream).

"I was dreaming that I was driving a car. Some criminal had passed in front of me and looked at me as though he was planning to hurt me. I can't remember why. Afterwards, my rabbi said: “Now you can see – I was right when I told you it was better not to have a driver's license because if you have a car you go out to the open world and there you meet people. And you are dangerous. I started crying".

"I woke up hearing knocks. I understood that those were gunshots and was afraid that bullets would hit me."

"I was dreaming I intended to kill my brother. Afterwards, they took me to a jail. I see him there. He is in handcuffs, and they say he is going to a jail too."

"I am with my whole family, as if my parents are not divorced. Nobody pays attention to me. I am calling my father: Daddy, Daddy! He doesn’t hear me. They mistreat me, ignore me. I am trying to draw attention for about half an hour. Finally my sister says to me: “If you want to wake up pinch yourself”.

Here again the process of moving away from collective figures to personal representations parallels with the improving organization of behavior and thought processes observed on the clinical field.

On the other hand, there were series of non-evolving dreams showing an arrested movement in the unconscious: the patient is a woman in her forties suffering from a long standing resistant psychotic depression and admitted following several suicidal attempts.

"I see my father holding me and my sister and we are all in peace (the sister had committed suicide a few years earlier). We all walk in the mountains playing and having fun. I was at the age of 10-12 in the dream".

"In the dream I could see that my sister was playing and hiding somewhere. She was not at home. I saw in the dream that she left for a few days and came back".

"I saw my sister coming back to life. I asked her where she had been, where she had been hiding all this time. She said that she had hidden inside the mirror. Then I woke up."

Discussion

So, what are the conclusions we can draw from these examples. To our knowledge, there are very few, if any, descriptions of dreams of psychotics and of their relevance to the treatment of psychotic conditions.

From our observations we can deduce that acutely psychotic patients have difficulties in relating dreams, in discerning their inner reality as shown by the narrative of the dream and their external "real" psychotic experience. We have observed that the ability to tell a dream shows a better organized psychosis or maybe it is sign of a disease process on the way to recovery. Moreover, many times we could observe the improving clinical course as it was noted objectively parallel to the evolving process taking place in the unconscious. In other cases a "stuck" clinical condition of a patient showed the same stagnation in the series of dreams. Are these just synchronous phenomena? Phenomena not connected taking place the same time? Of course this is not the case. We believe that organizing and relating a dream requires investment of libido. It is an active effort to keep in touch with external and with internal reality simultaneously, an investment of energy aimed at improving the capacity of the ego to observe. It is directed on a strengthening of the ego and an initiation of a process aimed at reversing the "abaissement du niveau mental" which characterizes the psychotic process. We suggest therefore that asking psychotic patients of their dreams and encouraging them to tell dreams, we help them to distinguish between the psychotic production and the dream. A kind of creating the world anew, marking a line between light and darkness.

At a first glance, this recommendation seems contrary to the Jungian legacy. Jung suggested, in cases of threatening signs of psychosis and certainly in psychotic phases, precaution, a strict avoidance of any concern with the contents of the unconscious, especially with dream-analysis. He advocated a reestablishment of personal rapport, he was very much in favor of helping patients to be at a sufficiently safe distance from the unconscious, encouraging them to draw or paint a picture of the psychic situation. Doing so, he claims, allows a distance from the internal chaos, and the "tremendum" is made more harmless and more familiar.

Conclusions

We do not recommend dream-analysis with psychotic patients, we believe that for dream-analysis an ego well anchored in reality is needed, and this is certainly not the case when working with the psychotic patients. Here we are in line with Jung's teaching. Therefore we did not elaborate on the content of the dreams in this presentation. We only observed that collective and religious themes appear very frequently in the dreams of the psychotic participants in our group study. We can state as well that no fundamental difference was observed between the dreams collected here and dreams we are used to hear in our regular practice. It is not on the basis of dreams that psychiatric diagnoses can be established.

But we do advocate encouraging the psychotic patient to tell a dream because of what the dream is. We advise the therapist who ventures in this difficult task of working psychotherapeutically with psychotic patients to help the patient delineate the dream, and in so doing to assist him in restoring the reality testing.

References

1. Andrillon, T., Nir, Y., Cirelli, C., Tononi, G., Fried, I.( 2015): ”Single-neuron activity and eye movements during human REM sleep and awake vision”. Nature Communications, 11:6, 7884.

2. Jung, C.G.(1939): “On the psychogenesis of schizophrenia”. Journal of Mental Science, 85, 999-1011.